In the past year, with a daughter struggling in middle school, I’ve had occasion to reflect on the various evils of various educational systems. And of course Woodstock School is much on my mind, as I consult live and printed sources to try to understand what makes that particular school great, preparatory to writing a book about it. I don’t have any answers – I surely wish I did! – just many questions.

My own scholastic experience was vast and varied. By the time I finished high school, I had attended 10 schools, all of them quite different from each other. Some were good, some were not. At the time I was hardly a reflective participant in the process, but I’ve been thinking it over, trying to pinpoint what made the difference between the good schools and the bad ones.

Mrs. Stevens’ School, Bangkok

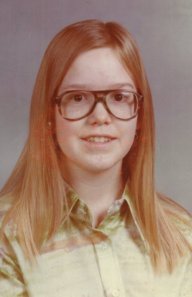

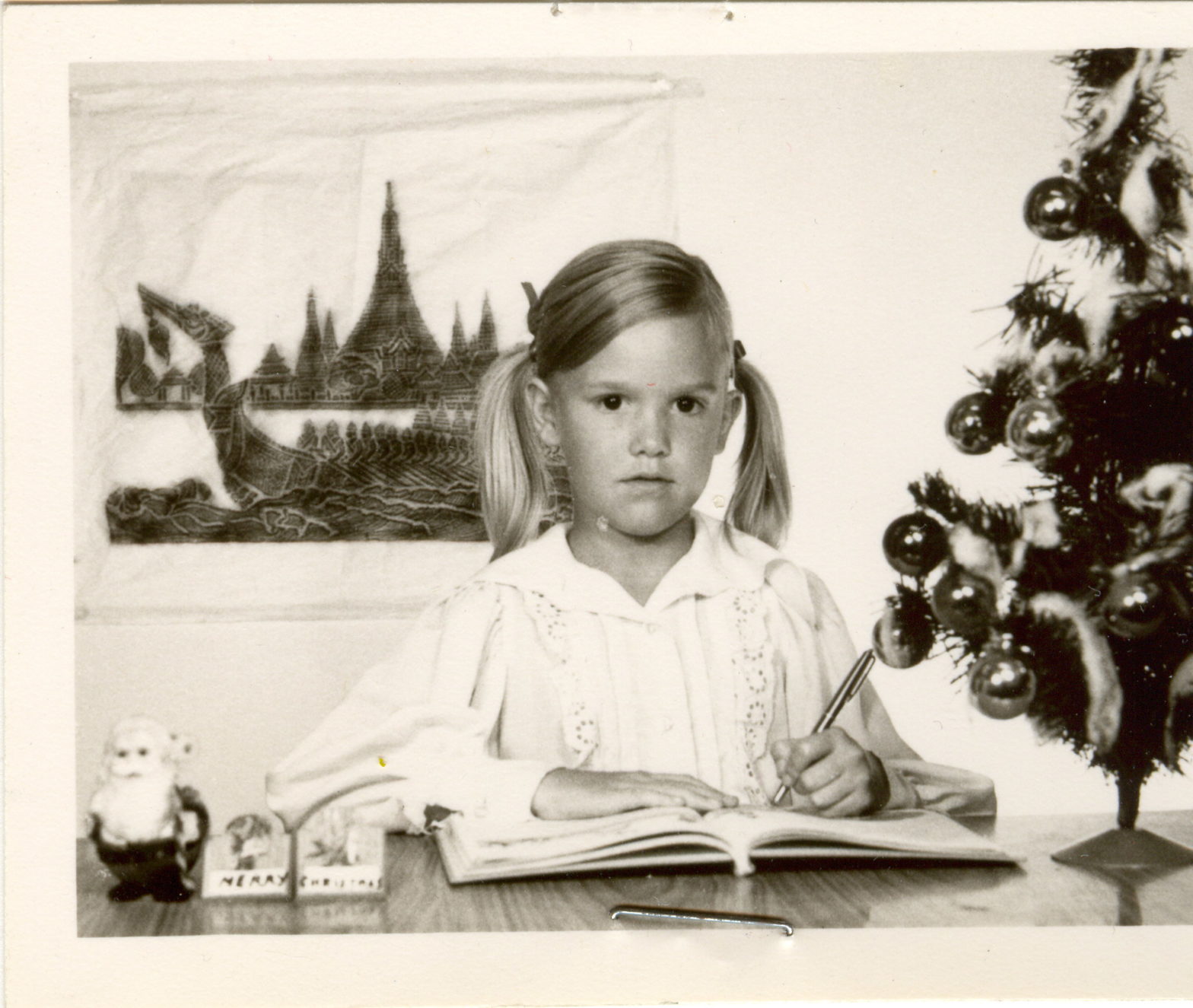

Mrs. Stevens’ School, where I attended 1st and 2nd grade in Bangkok, was a small, private school run by an Anglo-Indian woman. I don’t know what her qualifications were, but I remember being enthralled by the number of children’s books she had. (It wasn’t easy to get English-language books in Bangkok in those days, so I owned very few, and was an avid reader.) When prospective new students and their parents came to see the school, Mrs. Stevens would trot me out to read for them as an example of what could be achieved. I dimly realized that there was something fishy about this: shehadn’t taught me to read – my mother had.

Although I was a biddable child, Mrs. Stevens couldn’t tame my hair. Straight, fine, and prone to tangles, it hung down in a floppy fringe (bangs, to you Americans) that got in my eyes, so I was constantly pushing it back while reading to impress the parents. Mrs. Stevens felt that this distracted from my performance, and nagged me to tell my parents to have my hair cut. I don’t know whether I failed to report this message (forgetfulness? rebellion?), or they failed to act on it, but finally she could bear it no longer, so she cut my hair herself, badly. That was too much for my parents, so I left her school.

International School Bangkok (ISB)

I then attended the International School Bangkok (ISB). At the time, due to the large population of servicemen’s families and other US government employees in Thailand to support the war in Vietnam, the students and teachers were mostly American. We were given a smattering of Thai language and culture, but for all practical purposes we could have been in any school in the US.

For 3rd grade I had a crotchety old lady teacher who should have retired earlier. She was the cause of my first overt rebellion against authority. We were supposed to do library research about George Washington; I failed to see the charm or the point, and told her I’d rather do research on someone I actually cared about, such as my own father.

For 4th grade, I took part in/was subjected to an educational experiment. Four 4th-grade classes were put together with four teachers in one enormous room, where we would circulate to different areas for different subjects. This was known as the “pod” system.

What were they thinking? One hundred nine-year-olds in a single room? It was chaos. But I appreciated that; it was easy to get lost in the crowd. I could slip away from subjects I didn’t like, such as math, and hide behind a partition with my best friend Kathy, where we would read or draw or write stories. I remember liking some of the teachers, especially Mrs. Johnson, even though she did teach math. She wrote a note on my report card which has achieved the status of family legend: “We will all be glad when Deirdré decides that math is here to stay.”

Liberty School, Pittsburgh

Then my parents divorced, and my father and I moved to Pittsburgh, where he would go to graduate school. He didn’t have much money, so we lived in an apartment in an iffy part of town, and I went to Liberty, the local public school.

The change was catastrophic. I had been living in a huge house in Bangkok, with a big yard, two maids (who also acted as nannies to my infant brother), three cats, three kittens, two dogs, fish, a snake, two parents, and a baby brother. I suddenly found myself alone in an apartment with my dad.

Living with Dad was fine, though we ate a lot of tuna casserole, and I had to wash all the dishes. The problem was that I had nothing in common with the kids at school, who mostly talked about football, baseball, and hockey. They thought me an awful snob when I talked about my life in Thailand, the only life I had known. I was different, so they teased me. In response, I showed off my intelligence; that was a certainty I clung to, about the only one I had left.

I continued to rebel against authority. I refused to recite the Pledge of Allegiance, then standard practice in some American schools. “Under God”? I didn’t believe in God. “One nation, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all?” My parents had been involved in the Civil Rights movement in Louisiana and Texas in the 1960s; even at age ten, I knew how little truth there was to “liberty and justice for all” in America.

I survived 5th grade, and even made a couple of close friends, so I started 6th grade at Liberty willingly enough. But someone in authority had had a bright idea: put the slower 7th and 8th graders in the same classes as the faster 6th graders. I was one of the latter. The older kids of course resented being lumped in with younger kids and publicly branded as stupid, so they sought to put us in our place. My instinct for self-preservation not being well-developed, I reacted to their teasing, letting them know that I was a lot smarter than they were. The abuse rapidly became physical. I came home one day bruised all down one side of my body, from being slammed against a locker in the hall by an older girl who didn’t like my attitude. My dad withdrew me from the school.

Shady Lane, Pittsburgh

I then went to Shady Lane, an “alternative” school. Classes were small and the atmosphere generally pleasant and cooperative, but I was scared by now, and tended to avoid most of my classmates. I read a lot (something that teachers always liked), and I don’t remember being made to do too much that I didn’t like academically, though I did finally conquer fractions. And I met Anna Levy, destined to remain my best friend for several years.

Shortly after Christmas, however, my dad was hospitalized as a result of some gastrointestinal bug he’d picked up in Mexico the previous summer. I had spent that summer with my aunt Rosie in Texas, and it was to Rosie that I now returned. She lived (and still does) in the country, outside the tiny town of Coupland, then famous for its barbecue.

Coupland School, Coupland Texas

I joined Coupland School, where the 5th and 6th grades were taught by a single teacher in one classroom, and even so there were only about 12 of us in the room. By this time I was so afraid of my peers that it took me a long time to realize that these kids genuinely meant to be kind to me. I spent recess and lunch periods in hiding, reading.

We participated in a regional spelling bee. I didn’t make a single mistake, so when it came time to give prizes for our age group, I waited expectantly. The man giving the prizes picked up the blue ribbon, glanced at the name on the back, frowned, and put it down. He then went through all the others, down to sixth place, and my name was never mentioned. I stepped forward and pointed to the blue ribbon. “I think that’s mine,” I said. It was; he just hadn’t known how to pronounce my name.

Ellis School, Pittsburgh

In late April I returned to Pittsburgh for my dad’s wedding to Nancy, and didn’t go to school for the remainder of that academic year. For September, my dad had somehow got me into Ellis School, an expensive private girls’ school where he had been working part-time in the library. They suggested that, since my previous school year had been very disrupted and Ellis was academically demanding, I should repeat the sixth grade. I don’t recall minding this particularly; I was emotionally less mature than my peers, and felt better able to cope with slightly younger girls.

Ellis was where I finally got to grips with a lot of things, including math. Within a few months I was sailing through all the work, usually getting my homework done in class while the teacher was still lecturing. I liked the English teacher, who didn’t mind that during her classes I drew stories in picture form; she even asked me to hang them up and explain them to the class. NB: I could and did listen while I drew; drawing helps me concentrate on what I’m hearing.

I liked the music teacher, who let us sing songs from musicals. Science class was also excellent: we built electrical circuits, and for human anatomy there was a dummy torso that you could open up and take out the organs, stuck in on brass pins, to see how it all fit together.

Ellis had the excellent facilities and equipment you’d expect of an expensive school, but perhaps what really made the difference was that the teachers took a real interest in the students. The English teacher took us to see a local production of “Camelot,” and I laughed at Lancelot’s arrogance in the song “C’est Moi.” The teacher said to me gently: “Maybe your classmates sometimes see you that way.” I thought that over. Maybe they did. I still defended myself from teasing by letting the teasers know that, whatever might be weird about me, I was certainly smarter than they were.

Reizenstein, Pittsburgh

Reizenstein, Pittsburgh

My dad couldn’t afford another year of Ellis, so for 7th grade I went back into the public school system. I was bused to a newly-built school, Reizenstein. Since the school was brand new, we had the opportunity to determine important things like a name for the sports teams. Which was a stumper: what goes with “Reizenstein”? The principal liked “The Rise-and-Shiners,” but we all thought that was stupid.

Reizenstein, with all its newness, seemed to hold out hopes of a better school experience for me: at this school, everyone was a new kid. I was put into accelerated reading classes and a “gifted and talented” program. This was cool; there were only five or six of us in the class, and we learned to dance the tarantella. I wondered about the academic value of this (though I now live in Italy, it’s a skill I’ve never needed), but didn’t complain: it beat being bored and teased in regular classes.

I still had problems with my peers. I was far from being racist, but many black girls seemed to have it in for me. After a verbal battle with one, we both ended up in the principal’s office. In the midst of his thoughtful lecture about getting along, we gave each other sidelong glances, sharing a moment of solidarity over how unlikely this was to resolve anything.

The school launched a busy program of extra-curricular activities. I was thrilled at the chance to participate in a production of “Oliver!” We first listened to the songs and were told the story, then it was time for auditions, singing one of the two songs we had learned. After auditioning several dozen kids, the teacher decided there wasn’t any more time; she would assign the parts, and the rest of us would be in the chorus. This was unfair, especially to me: I already knew all the songs by heart. So I insisted on auditioning, sang a song the group hadn’t yet learned, and was awarded the role of Bett (a minor part, but a step up from the chorus).

Unfortunately, only a week or two later I learned that we would be moving to Connecticut, where my dad had a new job as director of a drug rehabilitation program. So I never got to be in the show.

West Rocks Middle School, Norwalk CT

Dad’s job was in Westport, a wealthy bedroom community for NYC executives, whose kids had enough money to buy expensive drugs. For parties, these kids would clear out their parents’ medicine cabinets, dumping all sorts of pills into a punch bowl, from which they would swallow them by the handful. By the time they reached the hospital, it was difficult for the doctors to know how to treat them… but I digress.

Dad worked in Westport, but we lived in Norwalk, a far less glamorous town, where I attended West Rocks Middle School. As usual, I made one or two good friends, and was brutally teased by everybody else. I had a few good teachers. Mr. Aylmer, an Irishman somehow transplanted to Connecticut, was an inspiration for social studies. I scandalized the class by reporting on a controversial article about how fast food wasn’t good for you, a fact that my classmates did not want to believe. (They’d have been even more shocked had they known that the article was published in “Penthouse,” a magazine largely devoted to pictures of naked women.)

Another good teacher was Bruce Schwartz, for English, whose ambition was to write musicals – I could certainly empathize with that! Norwalk is only a short train ride from Broadway, so he took us to see some shows, including the wonderful original production of “The Wiz” (ignore the stupid movie with Diana Ross and Michael Jackson). Yes, I saw Hinton Battle on stage, 25 years before he played a singing, dancing demon on Buffy.

At the end of 7th grade, I auditioned for and won a place in a small, elite school choir for the following year, so I had that to look forward to when 8th grade began. But I never got to sing; within a few weeks of the school year beginning, it was decided that we would move to Bangladesh. Trying to explain this to my peers was interesting; they had never heard of Bangladesh. “It’s next to India,” I said. No light dawned. Finally one kid said brightly: “I know! You’re moving to Bangladesh, Indiana!” (It could have been worse: my dad had also been considered for a position in Ougadougou, in the country then called Upper Volta, now Burkina Faso.) What happened next was covered recently in Meta-History: I did 8th grade on my own by correspondence through the Calvert School, then I went off to boarding school.

Why Do We Have Schools, Anyway?

So… what can I distill from all these experiences, plus my far happier years at Woodstock?

I once read that school as we know it today was designed at the time of the industrial revolution, to teach people to work to a schedule and obey authority; this training was needed to turn independent farmers into factory employees (and soldiers).

In general terms, we assume that the purpose of school is to prepare people to be productive members of the economy. However, the economy is now moving so fast that it’s difficult to predict what precise skills will be needed. Many of us are now doing jobs that simply didn’t exist when we were in high school, or even college.

Some would say that an important role of school is socialization: teaching children the laws, rules, and norms of the society they live in. For those who don’t easily fit in, this can be a brutal process – brutality largely supplied by one’s peers. Children are naturally conservative, and seemingly take to heart the Japanese adage: “If a nail sticks out, hammer it down.”

Woodstock School, I believe, has the right answers to both preparation and socialization. The Woodstock experience taught us to respect and enjoy differences. And, between Woodstock and the international lives that most of us already led, we learned to embrace change. I’ll elaborate on these themes in future; both are important to the Woodstock 150th Anniversary book I’m working on (project abandoned by the school, at least at of 2007). And maybe we’ll find a way to apply the lessons of Woodstock in other schools.

Deirdre, I know this post of yours is more than a decade old, but it came up in a google search I did looking for mentions of Mrs. Stevens’ school in Bangkok. My sister (Tristin) and brother (Danny) and I (Alison) were there in the 1965-66 school year. I remember being very afraid of Mrs. Stevens (though she never tried to cut my hair!), but I had some other teachers there that I really liked. I started the school year in first grade but ended it in third due to the very fluid class placement rules there. Were you there during that year?

I would have been there in 67-69 I think – our first two years in Bangkok. Yes, I was afraid of Mrs Stevens, too! Then at the International School Bangkok I got an ever scarier old lady teacher…

I was there in 70 and 71 , I’m not even sure it was an accredited school. Mrs Stevens spanked us and we also were made to kneel on hot pavement and recite poetry. She always tried to move kids up grades and then show them off to prospective student and parents. A six year old in 3 rd grade ! Her CHristmas pageant was such a huge deal to her as was how you looked. Such a sick place.