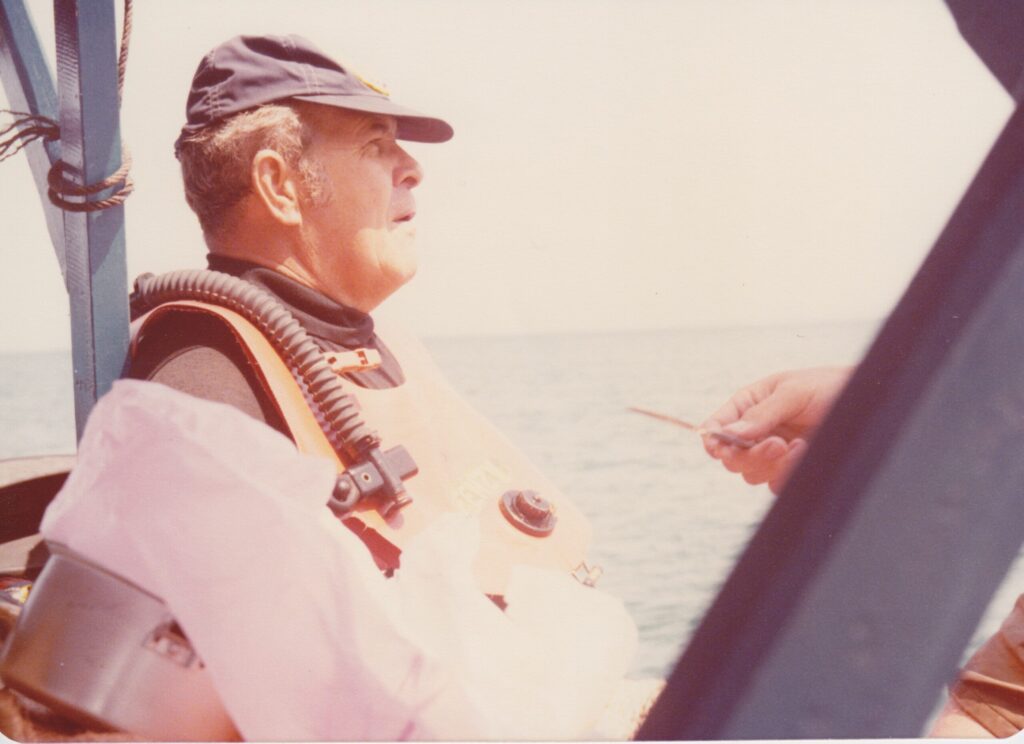

During one of my winter vacations from Woodstock, when my dad and stepmother were living in Bangkok, my dad and I did a scuba diving course. Dad had started diving during our year in Hawaii (1966), and I’d been hearing his stories about it for as long as I could remember. Getting certified together sounded like a fun father-daughter activity, and it was.

Our instructor was “Dusty” Rhodes, who had served with distinction in the US Navy during the Vietnam war, and had then settled in Thailand. I did not realize until years later that the preparation he gave us went far beyond typical scuba instruction.

Lessons started with theory, taught in a classroom. I don’t remember much, except the unit where Dusty covered various potential hazards in the water, including sharks. There was a graphic illustrating the typical circling the head movement that reef sharks make to warn intruders away from their territory. Dusty said that we wouldn’t have to worry much about aggressive sharks in the coastal waters of Thailand. Among other odd jobs, he had served as a consultant on a Thai action film which included underwater scenes; he had had a hard time getting the sharks to come out and look angry. (As it turned out, I never saw a shark at all.)

After theory had been covered over several lessons (and our grasp of it tested), our training moved to a hotel swimming pool. We first familiarized ourselves with the equipment, learning all the parts and how to wear them. Then Dusty had us jump into the pool with our gear over our arms, not yet properly on us. We had to sink to the bottom of the pool and then put on our gear. Dusty explained that this was what Navy divers had to do in combat situations – they’d be brought in by a helicopter flying low with no lights, jump from the chopper into a river in pitch darkness, then don their gear at the bottom of the river. Obviously, you had to do this fairly quickly so as not to drown or be forced to the surface.

Another exercise had us all seated in a circle at the bottom of the pool, sharing and then swapping our gear to simulate the situation of someone’s breathing apparatus failing while deep under water. One classmate ran into a problem at this point: she was too buoyant. She wasn’t particularly fat, but somehow her total body mass was lighter than the water: she couldn’t get down or stay down without swimming hard or putting a lot of lead weights on her diving belt. She eventually quit the course in frustration. I suppose she could console herself that she wasn’t ever likely to die by drowning.

The final weekend of the course required us to be on open water. My dad and I drove to Pattaya Beach. Typically for Dad, he had not made reservations nor scouted out the situation in advance, so we arrived to find all the hotels booked by a conference or such (Pattaya was a lot smaller 40 years ago!). Driving around, we finally found a remote hotel that usually rented by the hour, and even that was almost full. They offered us a room which upon inspection proved to have one large bed and a mirror on the ceiling. Dad forcefully declined, explaining that I was his daughter. The hotel owners smirked knowingly at this, but eventually found us a small bungalow with separate rooms. It may have been someone’s home, temporarily vacated.

An added complication for me was that I had just gotten my first period (at age 16). I wasn’t at all freaked out about this (mostly annoyed), nor did I have cramps. But I’d be out in the water for at least 8 hours with no access to a bathroom, and I didn’t want leaking blood to say “Come get me, sharks!” Most girls use pads for a while when they first get their periods, before graduating to tampons, in part because they feel or are expected to feel some degree of ick about touching themselves “down there”, let alone putting something “up there”. I didn’t have that hangup, which was a good thing as I also didn’t have that option – I had to use tampons, and for our days on the water I had to use two inserted at the same time. That was when I learned that vaginas are stretchy.

We went out in a fishing boat that Dusty had hired. Our first open water test was to swim (on the surface) between two of the islands. It was a long swim, though much easier with fins on. As I swam, the seabed below got further and further away until all I could see was millions of little motes rising up in the rays of the sun that penetrated the murk to a few meters down. Then came thousands of jellyfish, also rising toward me from the depths. Fortunately all I ran into were small moon jellies, which just stung a bit on my bare arms and legs.* Later in the day my dad encountered a man o’ war and had to be treated for the far worse stings of tentacles that wrapped around his arm (if I recall correctly, the treatment was vinegar). During the second dive he blew out an eardrum, which was even more painful.

Our group was small, but happened to include another girl my age, a South African named Fernanda. So she was my diving buddy. On day two we did two dives, and Fernanda and I were able to stay out longer than anyone else – apparently younger people don’t consume their air tanks as quickly.

I enjoyed being underwater: skimming along above the reefs felt like flying, and I was fascinated by the sea life. There were too many sea urchins, but I liked their little blue eyes peering out from between and below their black spines. I did not have an underwater camera (in those days, only well-equipped expeditions like Jacques Cousteau or National Geographic had such), so all that is only fading memory by now. I remember getting close to a shore where the waves roiled up golden sand, and I loved being able to dive below the roll of the waves back to stillness and quiet.

Another thing I like about diving is that, as a sport, it does not require fast reflexes or physical grace. If anything, you’re usually better off during a dive emergency if you take time to think about what is going on and how to deal with it, and don’t react too quickly. Pop to the surface from too far down and you’ll get the bends – at best horrifically painful, at worst potentially fatal.

Not long after the course concluded, it was time to go back to school in the Himalayas. One of my least favorite teachers was our PE teacher, because she made it only too clear that I was one of her least favorite students. I wasn’t good at any of the sports we did in class and clearly never would be, so she had no interest in me. Within the first week of school I marched into her office and shoved my new diving certificate under her nose. “See?” I said fiercely, “I can do something!”

* if I recall correctly, the cover photo of me was taken after that gruelling swim