^ top: “More taxes on your savings? No, thanks!” To which someone has responded: “What savings?”

Italy doesn’t yet have a large enough Internet population to spawn interesting multimedia political parodists like JibJab. But citizens nonetheless find ways of talking back to their politicians…

Note: All these pictures were posted by readers on the site of Il Corriere della Sera (under “Elaborazioni fotografiche”).

Forza Italia (Berlusconi’s party) have done a series of posters with the theme “No, Grazie” (No, thanks) about all the terrible things that will supposedly happen if the left is elected.

^ Same original poster, this time with the response: So’ finiti, Roman dialect for “Sono finiti” – they [the savings] are finished (used up).

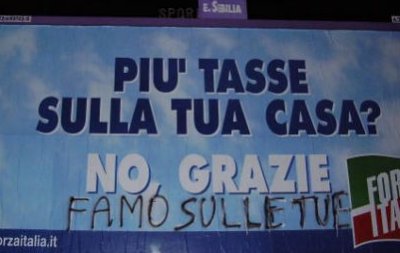

^ “More taxes on your home? No, thanks.” “Let’s tax yours.”

Famo = Roman dialect for facciamo – let’s do it. Le tue [case] refers to Berlusconi’s homes. Homes plural – he has several. Not that this is unusual in Italy, but his are rather bigger than anybody else’s…

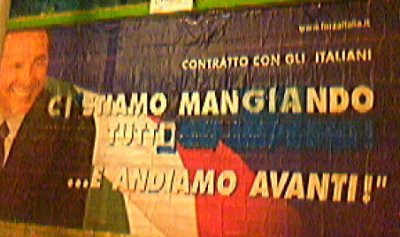

^ The original text reads: “Contract with the Italians. We are keeping all our promises!” Someone has inserted: “to our buddies.”

Final (original) line: “And we’re going ahead!”

^ The same poster, altered to read: “We’re eating everything – and we’ll continue!”

^ “Neighborhood police and carabinieri are now in every city” …and they still haven’t found you.”

^ This one originally read: “Let’s choose to go on/move ahead.”It now says: “Let’s choose to steal a lot.”

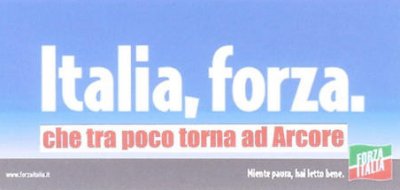

Forza Italia’s name is also a slogan, roughly translatable as “Let’s go, Italy!” (forza is what you say to urge on your sports team).

For this campaign they’ve turned it around so that it reads like an admonishment to a recalcitrant child: “Come on, Italy.” Or encouragement to someone very tired: “Come on, you can make it.”

With the added text, this translates as: “Hang in there, Italy – soon he’ll go home to Arcore.” (Arcore, near Milan, is the site of Berlusconi’s biggest villa.)

^ Casini, head of another party in Berlusconi’s coalition, claims [to have] a “A different idea.” Comment: “If only you had one.”

^ “More support for the family” …of Berlusconi.”

And, for the opposition, my personal favorite: