(Part 2 of Resistance is Futile: The Oracle Acquisition)

I, too, received well-meaning advice from several high-profile Sun people: my job would disappear because Oracle “doesn’t do community” in the same way Sun did. This was true: we were told early on that our community work would be handed over to the small Oracle team that managed relations with the wholly independent and self-funding Oracle user groups worldwide. The OpenSolaris and Java beer and pizza parties were coming to an end. During this time, I was forcibly appointed secretary to the OpenSolaris Governing Board, a job I would not have been enthusiastic about at the best of times (having little patience for formal committee procedure) – and this was, obviously, not the best of times for that group.

I performed my various sorta-kinda-marketing activities as a non-coding member of an engineering organization. Again, there was demonstrable value in what I was doing, but the oddity of it all made me vulnerable, especially in a more traditionally-minded company. In spite of Larry Ellison’s loud proclamations that few Sun staff would be cut, I could only agree with Tim and Simon’s assessment that I would likely be one of those few.

In the midst of all this, in late August/early September of 2009, I broke up with Enrico, to whom I’d been married for 20 years. Yes, I believe in getting through all of my traumas at once. (Not to be dismissive of what was obviously a shattering event, but this is not the place to discuss it.)

Meanwhile, we in Solaris engineering had community and marketing activities already planned and paid for into early 2010, so we carried on with a “last waltz” desperation, waiting for the axe to fall. In the summer of 2009 I travelled to Brazil, New Zealand, Australia, and OSCON for Sun. In the fall, I helped run events at Usenix LISA in Baltimore and SuperComputing in Portland.

All this (and more) created so much video footage that I was paying Sun’s professional video contractors to edit my videos. I later learned that this work kept several of them afloat while Sun’s official marketing media activity was being shut down and handed over to Oracle.

We all got a taste of Oracle media and events showmanship at Oracle Open World in October, 2009.

The opening keynote session started with Scott McNealy, Sun founder, former CEO, current Chairman of the Board, and orchestrator of the Oracle acquisition. Against a backdrop of soothing Sun blue, he gave a sweetly elegiac talk aimed at the Sun faithful: “We kicked butt, had fun, didnʼt cheat, loved our customers, changed computing forever.” All true, I supposed, but the McNealy magic failed to sway me – I had missed his heyday at Sun and didn’t really know why his former employees loved him so much.

Scott exited, stage right (or left). There was a moment of silence, then everything turned scarlet, the music changed to a pounding rhythm, and Larry came bounding out. He gave a very aggressive speech in the trademark Ellison style about how the newly combined forces of Oracle and Sun (“but mostly me“) would beat the world – especially IBM and RedHat. At the very least, we were in for a change of leadership style.

I had pinned some hopes on the fact that Oracle’s top executive team was much more diverse (read: fewer white men) than Sun’s. I was particularly prepared to be impressed by Safra Catz, the co-president/COO, who had a reputation as a shrewd, no-nonsense businesswoman. She was stiff and clearly uncomfortable on stage, which was forgivable. But then, in reference to an Oracle partner that does retail analytics or some such, she mouthed a scripted line about “Oh, I love shopping.” Safra! How could you let them do that to you? This chipped away at my hope that Oracle might be ok to work for.

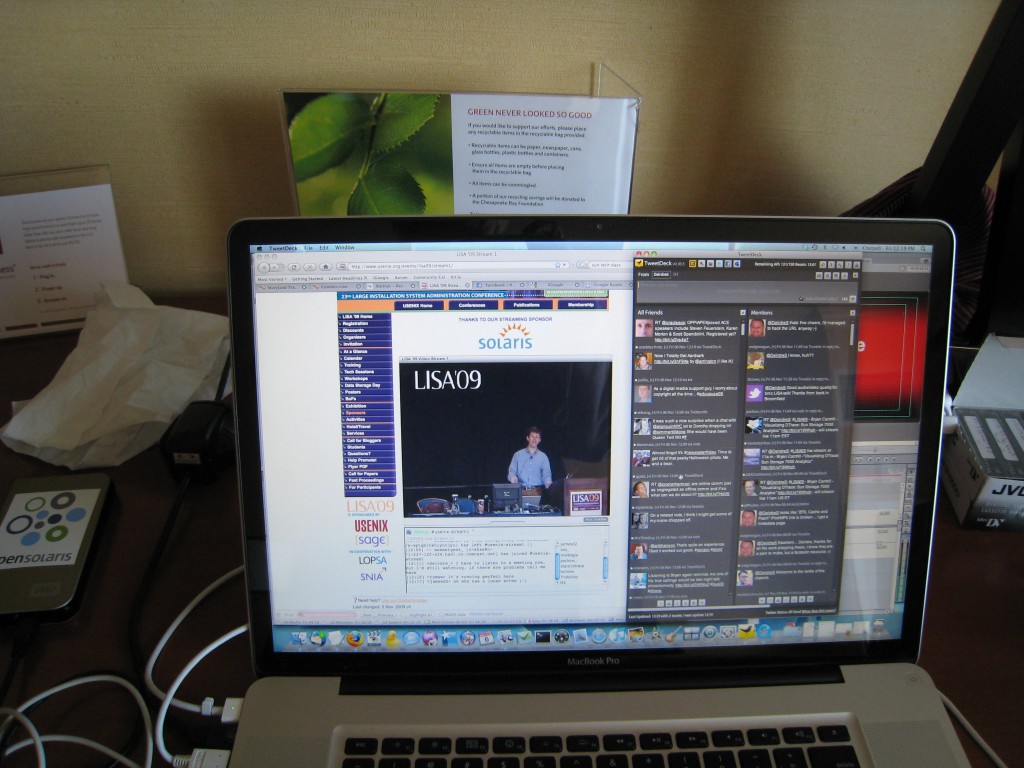

While at LISA, I got in front of the camera for once, in a conversation with Joyent’s Ben Rockwood about “conferences in general, open source communities, Solaris, OpenSolaris, Sun culture, Sun personalities, the value of video, social media…” I’m not sure I actually held out much hope by then that any of those things would be valued at Oracle.

A day or two after this, still at LISA, I learned that our small team (me, Teresa, and our manager, Lynn) were all being moved into the Solaris marketing organization. I remember half-consciously digesting this information while haranguing a Usenix-hired cameraman (via cellphone from my hotel room) to zoom in on Bryan Cantrill’s face during his keynote talk. I had barely even met Bryan then, but I wanted his video to look good.

When I was (not very often) back “home” in Colorado, living conditions were stressful. I was renting rooms in a large house from a Sun colleague who had recently had her boyfriend, also a colleague, move in with us. Wondering which of us would survive the transition to Oracle did not aid our already-tenuous household harmony. I had never planned to stay in Colorado long-term; I’d intended it as an easier transition back into the US from my quiet life on Lake Como, before tackling the hustle and bustle of Silicon Valley, where I would logically end up for the sake of my career. By early 2009 I had started thinking about making that next move, but the acquisition announcement had put all transfers and promotions within Sun on hold, so for the moment I was stuck.

From the contact we had with Oracle (for us non-exec types, largely via “town hall” conference calls), it was becoming clear that Sun and Oracle were not well matched in corporate culture. One such call was a “we’re number one” pep talk from an Oracle sales exec. I turned to my colleagues listening alongside me in a Sun conference room and said: “When do we all line up for our testosterone injections?”

During a visit to the Bay Area in January, 2010, I met with the woman in charge of Oracle media. It was immediately clear that I would have to fight the “professional vs amateur” video battle all over again; Oracle’s attitude was that only VPs and higher in the corporate chain were worth putting on camera. Not surprisingly, two of Sun’s three video hosting services would be killed off, and the remaining one would be largely inaccessible to plebs like me. “You can put that stuff on YouTube,” she said dismissively. This would cost me a lot of work: YouTube limited me to ten-minute clips, while some of my videos were three hours long!

“What happens to all the material already published?” I asked, thinking of the many hours of Solaris history I had captured, engineers talking in depth about what they had created and why – information that might never be available again.

“We discard it all, not worth rebranding,” she said indifferently.

I pointed out that many of my videos were deeply technical and would continue to be relevant at least until the release of Solaris 11. She grudgingly agreed that I could add an Oracle video intro onto each video by way of rebranding, and keep them… somewhere. Weeks passed before I actually received the file I needed to do this. I spent many, many hours archiving videos from MediaCast and SLX, the two doomed Sun hosts, editing in the jarring Oracle intro clip, and uploading the videos to new homes on YouTube and blip.tv. The lady had told me that the dozens of my videos on the Sun BTV site (the ones the professionals had been paid to edit for me) would have the Oracle intro automatically added, so I didn’t need to do anything with them.

My new director in Solaris marketing was not much of a backer on all this. He essentially patted me on the head and said, “Yes, your little community videos are cute, now go write white papers.” As a rule, I hate, loathe, and despise white papers, but that’s a rant for another day.

- Part 1: Resistance is Futile: The Oracle Acquisition

- Part 2: What to Expect When You’re Expecting – to Be Acquired

- Part 3: Fishworks and Me

- Part 4: Into the Belly of the Beast

- Part 5: The Last of OpenSolaris

- Part 6: Diaspora (not yet written)

- The 3rd Annual Solaris Family Reunion

- Part 7: Letting Go of a Beloved Technology