Kerry Bailey wrote in his blog recently:

…for some reason I can’t quite pin down I hate morbidly obese people. Just something about them fills me with this unexplainable anger. It’s like this weird sort of intolerance or racism that I’m not quite sure how to squelch. …

It’s somewhat ironic that I, as a gay man, have – in those instances – so little tolerance. Anyone got any ideas as to how to defeat those “ARRRRRRRGHGHGHG urges” ?

…which inspired me to write down something I’ve been thinking about for a long time.

It seems (to researchers, not just to me) that our brains subconsciously recognize people who are fit for us to mate with – or not – and we feel attraction accordingly. One instrument of this subconscious evaluation of fitness is the nose. I began wondering about this many years ago, thanks to experiences with my own sense of smell.

In high school I started “going with” Kris, who seemed well suited to me in geekiness, interests, etc. But an incompatibility soon became evident: he smelled wrong. Really bad, in fact. Not as in “didn’t take a shower,” but there was something about his personal smell that was absolutely repellent to me. I told him about it, and he tried new deodorants, colognes, etc., but nothing helped. I finally broke up with him essentially because of this. I felt mean and shallow about it: I liked him otherwise, but just couldn’t bear the smell of him. It seemed so irrational, and he was deeply hurt.

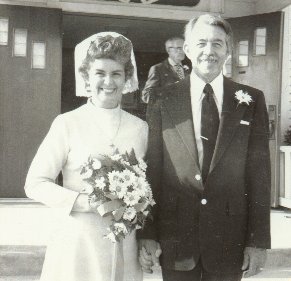

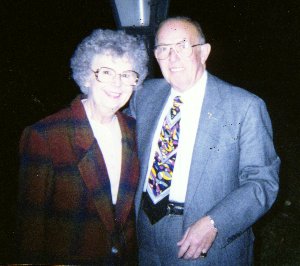

Years later, I met Enrico. We had a picnic together with the friend who introduced us, ended up at a party together the same evening, went to a concert on the green, then to a disco, then to his place and to bed. It was a hot summer night and, as I lay there with my nose literally in his sweaty armpit, I thought: “This guy smells good!” We’ve been together for 20 years now, 17 of them married, and have a gorgeous, healthy daughter. Obviously, he was a good match for me, and my nose knew it instantly. He still smells good to me today.

Some years later I read an article in the Economist on studies showing that humans unconsciously recognize via smell people with whom they are well suited to reproduce (suited in terms of immune factors – the more different these factors are between the parents, the healthier the offspring). In the words of Cole Porter: “It’s a chemical reaction, that’s all.”

An older woman friend to whom I told this story was relieved to hear it. She was dating a man whom her family thought ideal for her (interesting, well-off, etc.). There was no rational reason for her not to like this guy, and in fact she did like him – but not the smell of him, for which she felt the same kind of visceral repulsion I had felt with Kris. She was past reproductive age, but, nonetheless, her nose insisted that something was wrong, and she couldn’t get past this “irrational” reaction.

I stayed in touch with Kris because he was my Woodstock classmate, and saw him a few times after we graduated in 1981. I even hired him for an internship with the (tiny) company I was working for in 1987. But over the years he got weird and weirder, and I was increasingly uncomfortable around him. He died in California in 1999, having lost control of his vehicle on a highway at 2 am and crashed into a bridge support. An autopsy showed that he had had a long-standing brain condition that probably caused a seizure that night. I never got all the details, but another classmate who had stayed close to Kris (and who informed me about his death) was told by the doctors that a symptom of this condition would have been shaky hands – which friends had noted back in high school: we used to tease him about drinking too much coffee. This friend also told me that Kris’ co-workers had once complained to him about Kris’ smell and asked him to tell Kris to shower more often!

So it wasn’t just me, and it wasn’t just “he’s a weirdo” – there was something physically wrong with Kris which eventually killed him, and many people’s noses told us to stay the hell away, even when we liked him as a person and mating wasn’t an issue.

The conclusion I draw from all this is that perhaps we find certain people repellent (odoriferously or visually) because they are unfit for us to mate with, and our brains subconsciously know it and try to surface this knowledge: “No! Stay away!” This reaction is “irrational”: we don’t really expect to reproduce (or even come close) with everybody we meet. But these instincts are very old and ingrained, for good reason. Human beings (like other animals) have been selected by evolution to find attractive those potential mates who are reproductively fit; the traits that make people beautiful to us are (sometimes misleading!) signs of reproductive health.

I suspect that the converse might also be true: that we find certain traits (such as obesity) repellent because we have evolved to perceive those traits as symptoms of underlying problems (genetic or disease) that make a person less fit to reproduce.

This doesn’t mean that I believe obese people are genetically “wrong” or diseased, nor that I condone treating people badly based on their weight or anything else. But perhaps it explains why sometimes, in spite of our best ideals and intentions, we react negatively to some people, and can’t even explain why we do.