SuperComputing 08, held in Austin, Texas, was a huge show and a huge effort for many of us at Sun, especially Rich Brueckner. The Sun booth was humming, attractions included Scott Tokar, a magician, and Rich’s Java Chopper, complete with biker chicks.

The Glamorous Life

I’ve been told that some of my colleagues envy my job. I admit that it’s a lot of fun – and, when asked what I do, I focus on the positives – but right now I’m mostly tired. This month is the most intense I’ve yet had with Sun. Here’s what it’s looked like so far:

Oct 23: Flew to Minneapolis.

Oct 24, 27, 28: Filmed interviews with the SAM-QFS team at Sun’s Eagan, MN office.

Oct 29: Flew back to Denver, straight into meetings and more office time.

Nov 1-6: Filmed parts of Sun’s Data Management Ambassadors’ conference, fortunately being held near my “home base” office in Broomfield. Especially fortunate because I still had a lot to do organizing the SC08 Student party. Worked long office hours when I wasn’t behind a camera in a hotel conference room. (At least this particular conference room had huge windows, so I didn’t feel like I was in a cave all day.) When I was behind the camera, I was also usually doing something on my laptop, such as running the October stats on blogs and community websites.

Nov 8: Flew to San Diego.

Nov 9: Much-needed day off (it was a Sunday!), went to the zoo. Spent much of the evening on email, trying to finalize details for a blogging contest to be held around an important product launch the next day. Having received no word on a decision by 10:30 pm, I went to sleep.

Nov 10: Woke up and checked email again at 12:30 am, nothing. 5:30 am, still nothing, so I went ahead and mailed it, because the contest began at 6 am Pacific Time. Woke up at 7 to film an all-day ZFS Workshop at LISA.

Nov 11: Flew to Las Vegas for Sun’s Customer Engineering Conference. Lunch with Barton, toured the CEC show floor, hung out and had dinner with my OpenSolaris buds, declined to go to a late show with them, went back to my hotel room, watched House.

Nov 12: Filmed an HPC track that took most of the day, plus one other presentation. In the evening, participated in a Birds-of-a-Feather session on blogging. Disagreement was, er, lively.

Nov 13: After a very bad night’s sleep (my room at Caesar’s was right on top of a disco), got up at 4 am to catch a 6:22 am flight to San Francisco. Lynn picked me up, already dialed in to a staff meeting. In the afternoon, moderated the chat as Lynn’s presentation to Forum 2.0 was streamed online. Had a few ideas about how to do the moderator’s job better, will be writing about those later. In the evening Lynn and I had a meeting with Meena, then went back to our hotel for dinner. Had an extremely hot bath – the cold water didn’t work. At least the bed was very comfortable.

Nov 14: Up early again, interesting news on my iPhone. Hurried to get to Sun’s Menlo Park campus for Lynn’s second Forum presentation, then a dash to the airport for our flight to Austin. Arrived a little before 5, Diana about the same time from Denver, then ran into Matthew at baggage claim. Everyone’s coming to town for SC08. Got our cars, I went to Spankyville, where Ross was preparing dinner for a gang of us.

Nov 15: Up at 8 to catch up on emails and run some party-related errands, then on to film at Sun’s HPC Consortium all afternoon. Ended the day filming an interview with Dr. Jim Leylek. Had a quiet dinner with Dominic, went home and to sleep.

Nov 16: Up early again for the Consortium – first speaker of the day was Andy Bechtolsheim, so sleeping in was not an option! Left early (Peter took over the camera) so I could go help set up the venue for the party. More running around to pick up a tank of helium for the balloons and move our student helpers to the venue. Busy with preparations and then the party (which I think we can count as a success) until about midnight, went home and collapsed.

Nov 17: Woke up at 6:30, my brain immediately whirring madly through all the things I needed to do, though my body emphatically did not want to get out of bed. Made it back to the Consortium by 10 am to continue filming. Left again at 1:30 to go see Ross’ new home, have lunch, return the helium tank, and dash out again to film the opening of the SC08 show floor.

I hope to survive until Saturday, when I leave for warmer climes and something resembling a vacation. I should note that this month has been equally intense for practically everybody at Sun. We’re all looking and feeling a little ragged around the edges by now.

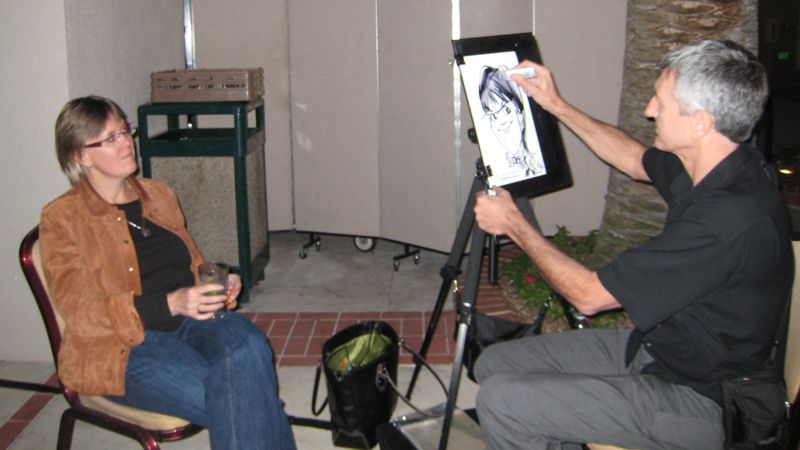

above: I did get to sit down long enough to have a caricature drawn at the OpenStorage Summit

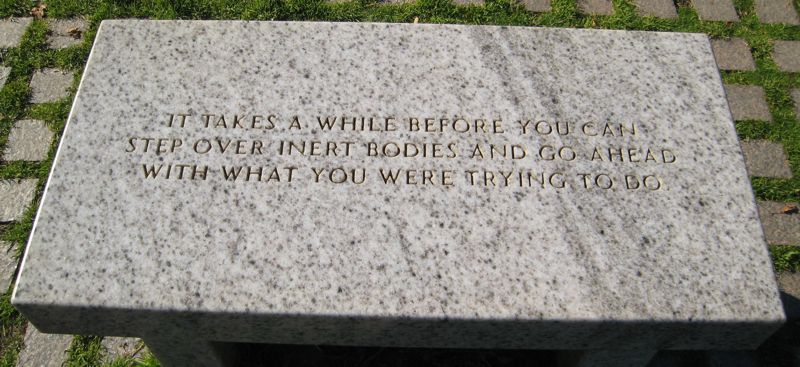

“It takes a while…”

Jenny Holzer, selections from The Living Series, 1989

Beh, truth be told – not that long.

Learn Italian in Song: A Casa d’Irene

At Irene’s House

Nico Fidenco

I giorni grigi sono le lunghe strade silenziose         The gray days are the long, silent streets

Di un paese deserto e senza cielo         of a deserted country without a sky

(ritornello)Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â (refrain)

A casa d’Irene si canta si ride         At Irene’s house [people] sing and laugh

C’e gente che viene, c’e gente che va         There are people who come, people who go

A casa d’Irene bottiglie di vino         At Irene’s house bottles of wine

A casa d’Irene stasera si va         Tonight [people] go to Irene’s house

Giorni senza domani e il desiderio di te         Days with no tomorrow and the desire for you

Solo quei giorni che sembrano fatti di pietra         Only those days which seem made of stone

Niente altro che un muro         Nothing else but a wall

Sormontato da cocci di bottiglia         topped with shards of broken bottles

(ritornello)Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â (refrain)

E poi, ci sei tu a casa d’Irene         And then there’s you at Irene’s house

E quando mi vedi tu corri da me         and when you see me you run to me

Mi guardi negli occhi, mi prendi la mano         you look into my eyes, you take my hand

Ed in silenzio mi porti con te         and in silence you take me with you

(ritornello)Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â (refrain)

Giorni senza domani e il desiderio di te         Days with no tomorrow and the desire for you

Nei giorni grigi io so dove trovarti         In the grey days I know where to find you

I giorni grigi mi portano da te         the gray days take me to you

A casa d’Irene, a casa d’Irene         At Irene’s house, at Irene’s house

(ritornello)Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â (refrain)

I’ve Been to the Zoo, Zoo, Zoo…

Who’s in captivity?

This young puma paced restlessly, completely uninterested in anything outside her cage, until someone came by with a couple of small children. Then the puma’s attitude changed abruptly: it was instantly clear where she saw herself, relative to small humans, on the food chain.

I love zoos, because I love seeing the animals. But zoos also make me sad, because I’d rather see those animals in the wild (a few times in my life, I’ve had that privilege), and so many species are becoming rare outside of zoos. But zoos like this one are contributing to conservation efforts, in hopes that someday we may be able to restore wild habitats and reintroduce the animals to them.