Some years ago Silvia, who had been one of our tech support team (of two) at Incat, paid me the enormous compliment of saying that she considered me a role model. This from a woman with a laurea in physics who holds a managerial position in a team supporting HP servers, and certainly never needed any advice from me on how to do her job!

I was extremely flattered, of course, but startled: I had never thought of myself as a role model for anybody. But it now seems that I am, and the job comes with responsibilities. Such as, um, eating free dinners and giving speeches.

Amanda Lorenzani (whom I’d enjoyed meeting at barCamp Roma), organized Italy’s first Girl Geeks Dinner, which took place in Milan last Friday. And she pulled it off magnificently: sponsorship from Excite, Dada.net, and San Lorenzo (who contributed the bubbly) ensured a very good dinner, complete with wine (though my request for a gin & tonic was turned down on the grounds that “then we’d have to give the strong stuff to everybody”).

At least 60 people were present, most of them, indeed, women. By the rules of Girl Geeks Dinners, women couldn’t be fewer than 50% of the guests: each woman attending can, if she wishes, invite one and only one man. (My date, by his own request, was Luca Conti.) After years of attending tech conferences at which women are always a minority and often silent, I was thrilled to meet and talk with so many smart, capable women. They had plenty to say for themselves, all of it interesting. Conversation flowed easily for most; I did what I could to involve those who seemed to be shy, though I was constantly distracted by new/old friends, and my feet hurt (I’m not used to wearing heels, but Ross had insisted I should).

We didn’t have a main speaker (as Girl Geeks Dinners often do although, surprisingly, they often seem to be men), but Amanda had asked four of us to each say a few words:

- Mafe de Baggis – long-time Netizen

- Frieda Brioschi – Wikipedian

- Beatrice Cristofoli of TechneDonne

- and, ahem, me.

My two-minute speech was neither as off-the-cuff nor as nervous as it probably sounded. I had been trying all day to decide how to translate that immortal line from Thelma & Louise: “You get what you settle for.” I finally settled on (which is different from settling for): Nella vita, ottieni quello di cui ti accontenti. And added, as my own closing line: Vi auguro di non accontentarvi mai – “I hope you never settle.”

Then I could relax and eat dinner and talk with people rather than at them. It was great fun to see in person someone I’d been following on Twitter, Svaroschi, who is heading off to grand new adventures in the Big Apple.

Almost everyone in the room had a blog, several specifically food blogs, which I will now go and read although it’s dangerous for me to do so, especially now when I have no time to cook.

Apparently I terrified at least one person in the room. Sorry about that – totally not my intention. I was a little weirded out – though extremely flattered – by people coming up to tell me they admire me, and/or like my site. Okay, it wasn’t that many, but it’s a strange experience nonetheless. Am I really somewhat famous, or just a legend in my own mind?

I was therefore a little manic, and very tired – had woken up at 4 am from jet lag, still wasn’t well (and destined to get much worse the next day), and had to get home to Lecco, with Luca in tow (as our house guest) at a not-too-unreasonable hour because we had to get up for rItaliaCamp. I hope for the next dinner I will be more relaxed and awake. There were so many topics in the air that I would have liked to hear more about.

Just one example: Beatrice came to represent TechneDonne, a project to study gender (in)equality in the world of IT. Among other things, they are asking themselves: “Is software different when women write it?” Interesting question. These are the folks who have asked me to speak at FemCamp in Bologna on May 26th; by then I hope to have had some opportunity to explore the roles of women at Sun Microsystems – in one week, I saw more women there than in any other tech company I’ve ever worked for or visited!

Another nice ego-stroke for me was that Tara (of Passpack) told me she’s loving my unfinished fantasy novel, Ivaldi. And she hadn’t even got to the good part yet! <grin>

It was altogether a fun and stimulating evening, and I would/will be delighted to see all of these people again, and hope to have time to talk with the ones I missed this time around. In fact, I’d like to do it more often – maybe we can do regional lunches or aperitivi in between dinners?

Update

April 2, 2007 – My pleasure in reminiscing on the joys of the dinner was somewhat soured by this:

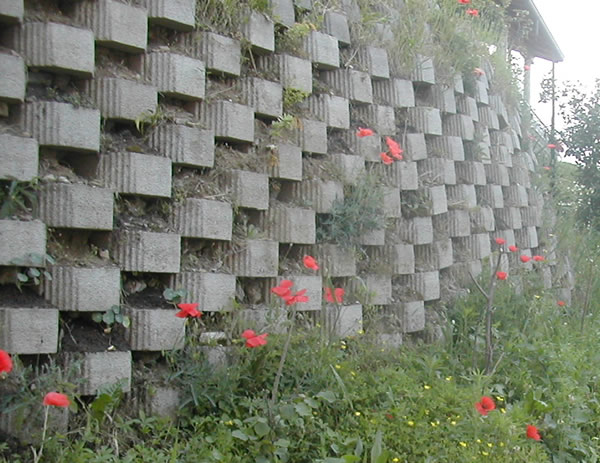

(photo by fullo via Pandemia)

This group represents a new (and very laudable) initiative by Alberto D’Ottavi, Stefano Vitta, Lorenzo Viscanti, Luca Mascaro, Chiaroscuro and Emanuele Quintarelli to encourage the development of Web 2.0 in Italy. But, boys, what’s missing from this picture? That’s right… girls!