Once upon a time at a small software company in Italy, I worked in an office full of women. This had come about because our CEO had gone to Silicon Valley, eventually taking with him all the (male) engineers, leaving behind the company’s administrative and accounting staff (all women), a graphic artist (woman), one language specialist/translator (woman), one tech support person (woman), one sales person (man), and me (tech writing, marketing, support, and other activities).

While the boss was off in the far west seeking his fortune with a bunch of Italian engineers and a new American crew for marketing and sales, the Milan office was still an important hub for the company’s European operations, so it couldn’t be left leaderless. There were plenty of people in that office who could have taken on the mantle of local general manager, and worn it well. (I soon began traveling to the Bay Area several times a year to work with the engineers, so I was not a candidate.)

But the boss, though a visionary entrepreneur, was in some ways an old-fashioned Italian man, and, though he never explained his reasoning, it seemed that he just couldn’t stomach leaving a woman in charge. So he appointed the only man in sight: L, the sales guy.

L was not a stupid man. He was good at sales and good with customers, but he was young, and relatively uneducated: it was then possible to quit school at the middle-school stage in Italy, and he had begun working young (to contribute to his family's income, I assume). He spoke no languages other than Italian, while the company did business worldwide. The situation was so blatantly absurd that customers and partners commented – frequently. Everyone who came to the office made the same damned joke about “L and his harem.” This, on top of the overall absurdity, annoyed me so much that one day I finally snapped: “The harem is [the boss]’s – L is just the eunuch!”

The boss eventually realized that L was uncomfortable and ineffective in the manager role. That, you would think, would have been an opportunity to appoint one of the women. But no. Instead, he hired a consultant, Mr A, to teach L how to be a manager.

I don’t know where the boss found Mr A, but oh, my, he was a find. He may have been the most blatantly sexist man it has ever been my displeasure to work with. He bragged that he kept his wife in line, and she wouldn’t dream of working outside the home or challenging his authority. He boasted that he would teach L how to keep a rein on us females, and was deliberately provocative in making these statements in front of us, perhaps to illustrate to L how it should be done. When he spoke to any of us women, it was usually to say something patronizing. His barrage was overt and unrelenting, but for the most part we shrugged him off. It’s doubtful that we would have found redress for harassment under any Italian labor law then (or now) in place.

In those years, the company used to attend CeBIT, the big technology show in Germany. The year before, we had sent a trio of our women, who were personable, attractive, technically competent, and had proved to be extremely popular among partners and customers at the show. Mr A decided that L should have that chance to shine. But he wanted to take me along as well, as someone who could actually have technical conversations, in English.

Though I already found Mr A plenty annoying, I rarely turn down opportunities to travel, so off I went. Mr A led me on a tour of customers and partners of which I remember very little, except that he talked incessantly and overstated everything – a trait that literal-minded geeks like me find hard to bear. Yes, we’ve all seen sales people who promise the sun and moon, but Mr A promised the entire damned galaxy. One meeting we had was with Dr. Somebody PhD, chief scientist for a large Japanese electronics company that made (among many, many other products), CD recorders. Mr A enthused to him: “Deirdré has been meeting with all your competitors, she can tell you what they’re up to!”

This was alarming. Yes, I worked with a lot of CD recorders and knew some of the people who made them, but… I’m sure the chief scientist knew far more than I did, and I wasn’t about to tell him his business or his science. Had I had any useful competitive information, it would be unethical for me to share it: we had OEM deals with all the manufacturers, and those included NDAs. I certainly wasn’t going to do something squirrely to try to justify Mr A’s hyperbole. I gently demurred, making excuses about how I really didn’t know much (which wasn’t true).

As we left the meeting, Mr A berated me: “Never contradict me in front of a customer!”

“Oh, but you see, Mr A,” I said humbly, “I grew up in Asia. I know that, in Japanese culture, women are expected to be modest. So I was playing to his cultural expectations.”

Mr A immediately waxed magnanimous: “Oh, in that case, you did very well!”

I said nothing more, but a careful observer might have noted a wicked glint in my eye as I thought to myself:. “Hoist with your own petard, you sexist bastard!”

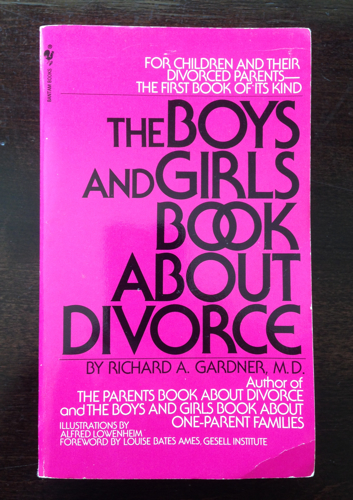

Back in Milan, one of Mr A’s ideas to build up L’s character and reputation was to have him write a book. This was a few years after the boss and I had written a highly technical book called “Publish Yourself on CD-ROM”. That book had indeed helped to make the reputation of the boss, the company, and our software (mine as well, though Mr A was supremely uninterested in my reputation). Mr A decided that L should also write a book about CD recording, in Italian, and he even lined up a publisher and had a contract with a deadline some months hence.

“The girls” told me about this project, which Mr A was at pains to conceal from me – not hard to do, as I was in the office increasingly rarely, in part because I couldn’t stand Mr A. I was both amused and offended. Apparently Mr A thought that writing a book of this nature was so easy, anybody could do it! But mostly, it was just (again) absurd: L didn’t even have a high school education in Italian. In order to actually write such a book, he would (for starters) have to be able to do the research in English.

After a few months, L was making no headway on the book project. The girls told me that Mr A then decided to pay another man to ghost write it, someone we already knew to be incompetent because he had previously been paid to do some tech writing work for us, but had failed to produce much. The girls did not bother trying to tell Mr A how disastrous this choice was.

A few months after that, it had become clear that this book was not going to be completed by the ghost writer, either. I was in the office on a rare visit one day when Mr A took me aside, told me all about the project, and tried to be nice (he thought): “Will you write the book for L? I’ll make sure your name is on the cover, after L's. I’ll even pay you.”

I was noncommittal, and did not say what I was thinking: “Putting his name alongside mine on a book that you expect me to write is actually an insult, and there is no amount of money that would be worth that.” I didn’t say no, but I didn’t say yes, either. But Mr A apparently thought I had agreed. Because he was the kind of man who hears “yes” even when you say “no”.

The next day I was working from home when Mr A had a staff meeting. He gathered everyone into the boss’s office, dialed me in on a speaker phone so everyone could hear, and triumphantly announced his big news: “Deirdré is going to help L write the book! Isn’t that right, Deirdré?”

“No,” I said flatly into the phone.

“What?” He couldn’t believe his ears. “What are you talking about? You said you would! Why will you not do this?!?”

“Because I don’t want to.”

Mr A slammed down the receiver. I wasn’t there to witness the scene, but the girls told me all about it (of course). Apparently he swore at the phone a lot after hanging up.

That was the last anyone heard of the book project, and the last time Mr A interacted with me in any way. Can’t say I missed him.