For several days last week, the spare bed in my studio was covered in piles of winter clothing. Mimma, the wonderful woman who cleans our house, would normally be unable to tolerate such a state of disorder, but she merely looked at it and observed: “Cambio di stagione.”

“Change of season” isn’t a precise period on the calendar – the weather varies from year to year, and this year has been unusually cold – but it’s a biannual ritual and, to some extent, a frame of mind.

Few Italian homes have American-style built-in or walk-in closets (though we all wish they did!). Some have old-fashioned wooden wardrobes, but more often you see enormous units that cover an entire wall and go all the way up to the (high) ceiling, custom made to fit the room, and installed by professionals. These are split into two vertical sections, with bars for hangers on both levels and shelves all the way to the top, which can only be reached if you’re standing on a ladder.

Hence the cambio di stagione, when you move your winter clothes up to long-term storage and your summer clothes down within easy reach (and, in fall, the reverse). It’s also a good time to review your wardrobe and realize just how many things you never wore the entire season – maybe it’s time for those to go to charity. So my bed was covered in piles to be stored and piles to be un-stored, while a good part of floor is still occupied by large bags of clothing to give away.

Cambio di stagione also refers to the period of unstable weather that occurs as winter turns to spring to summer to fall and back to winter, when you may suddenly find yourself over- or underdressed because the weather did something you weren’t expecting. It’s considered hazardous to your health: every little sniffle you get at these times is attributed to cambio di stagione, when your defenses are down as your body adjusts to the new season.

I used to scoff at this, but it makes sense when you consider that Italians live closer to the seasons than Americans do. American homes, offices, and public spaces tend to overcompensate for the weather, being overheated in winter and overcooled in summer. The net result is that you can (indeed, must) wear much the same clothing all year round, just throwing a coat over it in winter. You get from place to place in a climate-controlled car, and the only time that most Americans face the elements is when they choose to do so, for recreational purposes.

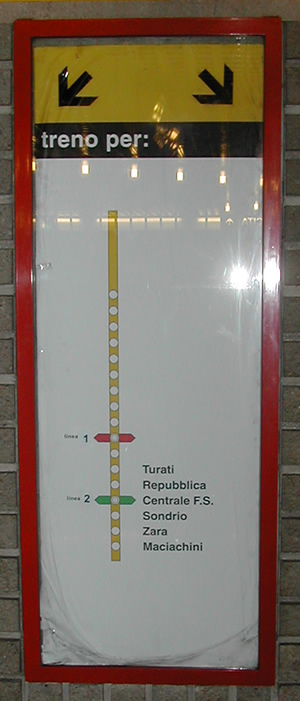

In Europe, people more often travel by public transport and on foot, so nature is a force to be reckoned with. Trains are usually heated, but the platform you stand on to wait for them is exposed and windy. Milan’s Central Station is made up of huge volumes of space, impossible to heat and bitingly cold in winter (though pleasantly cool in summer). Even the underground metro stations, with a wind howling down the tunnels, can be miserable in cold weather – and the trains surprisingly hot when packed with sweaty bodies at any time of year.

Hence our seasonal vulnerabilities. This year, the cambio di stagione got me with a vengeance: no mere sniffle, but full-on bronchitis. I must be becoming Italian.