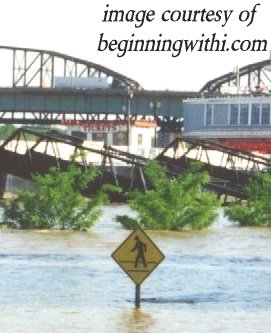

The Mississippi at St. Louis during a flood – only one rather special pedestrian could be expected to use this crossing!

All posts by Deirdre Straughan

On the Usenet: Supporting a Company in an Online Public Forum

My presence in online public discussion groups dates back to the CompuServe forums I frequented starting around 1993, where I helped customers with Incat’s CD-R software, and CD-R technology in general. I was eventually invited to start a section specifically for Incat software. Then a friendly user wrote me: “Hey, you should be out on the Usenet – they’re saying nasty things about your products.” (“What’s the Usenet?” said I…)

I was very visible on the Usenet until February of 2000, when I hired Adrian Miller to provide more technical know-how and detail than I had time to. Selected (nice) comments about both of us are given below; not all the comments were nice, but the nasty ones tend to be unrepeatable!

Even as early as 1995, the Usenet was plagued with trolls, flamers, and spam-mongers. So someone suggested a private mailing list, where folks interested in serious discussion about CD-R could get together in a more civil atmosphere; the CompuServe forums were fine for this, but were not open to non-members of CompuServe. So the Adaptec CD-R list was born…

Customer Comments on Usenet Presence

> on Mon, 23 Jul 2001, Deirdre’ Straughan wrote

> FYI, as of July 13 I no longer represent Roxio in these newsgroups or anywhere else.

From: mikah <mikah@nospam4me.com> Yeah, I know… and I’m still trying to figure out who I’m never going to forgive — you or Roxio.

10/15/95 – Your presence on the internet was a major part of my decision to purchase the HP system. Also, the Easy-CD Audio is a very nice utility. I hope that your merge with Adaptec will not decrease Incat’s innovation or responsiveness!

11/17/95 – Re: 2 second delay recording CD-DA: If only more people would post stuff that is that informative and enlightening

Subj: Write at once Section: incatsystems – January 25, 1996: I believe this is one of the best support forums and this is one more reason to buy Easy CD writer software.

12/8/95 – I really appreciate your activity on comp.publish.cdrom.hardware – many other discussion groups lack people who know and are willing to share their information. Makes a good impression of Incat systems, too.

12/19/95 – Incat probably has the best support of all the major companies. I have constantly seen you posting at various groups and your articles at some web sites. Your articles and posts have been extremely helpful in understanding the complicated nature of CD recording.

1/24/96 – I’m with Hewlett Packard support. I’m sending you this mail to say you’re doing a great job on the newsgoups

3/7/96 – …myself, my acquaintances and I’m sure others are always inclined to purchase from companies that make a presence on the net.

3/23/96 – I think it’s great that you guys consistently monitor the news groups and answer questions. Not many companies out there do that.

March 27, 1996 – …with Deirdre on line here, I felt sure that first-rate assistance was available; it was only a question of when, not whether, I could get help.

5/3/96 – Thank you for your participation in the newsgroups for CD-R. I purchased EasyCD Pro 95 (version 1.1.410) just because of your active participation.

I appreciate all the work you do here online. One of the reasons I bought the Smart & Friendly with Incat software was so that I could ask Deirdré tech support questions!

5/30/96 – …thanks for publicly supporting your product. I don’t see any names from HP tech support or Corel tech support on the cdrom.hardware newsgroup. It has made an impact on my decision about which software to buy.

5/27/96 – I would like to commend you and your company for having a presence on the internet that can actually be felt. A lot of companies out there say they have email and internet support and it is little more than what seems to be one person sending out one sentence answers that are not very helpfull.

6/28/96 – …I doubt if the 90 days trial will be necessary – I’ve been impressed by users comments in the comp.publish.cdrom.* newgroups and by the technical support given in your postings in the same forums.

August 13, 1996 – Your comments to everything posted here are always helpful and enlightening and this is one of the finest support forums I’ve seen.

9/19/96 – But did want to say thanks for your response. Your presence in these newsgroups (and the newsletter!) is much appreciated. I hope your boss realizes how useful all of this stuff is to us users out here!

17-Oct-96 – Thanks. You are doing a great job of keeping in touch with your users via the newsgroup(s). I wish all vendors had similar policies (and people to act on them so efficiently).

23-Nov-96 – Welcome Back.These newsgroups have not been the same without you 😉

Subject: CDR Advice! – 28 Nov 1996 – Newsgroups: comp.publish.cdrom.hardware – Deirdré — You’re doing a great job here, thanks for all the helpful posts.

04-Dec-96 – Deirdre’, I would like to thank you for your informative posts to comp.publish.cdrom.hardware. The support you provide there influenced my decision to go with Adaptec’s mastering software.

18-Dec-96 – I don’t know what your employer’s attitude is towards your interaction with the usenet groups, but I for one think it is an excellent thing…

…Though you are in a difficult position, as witnessed by the needless comments you received (wasn’t from me, hope you didn’t take them personally, but it is only human for them to hurt a little) and it would be impossible to conduct an online support group in this way from a corporate point of view, I hope you will continue to try to reach a happy medium. Your postings are always the first I read.

18-Dec-96 – nice to see you commenting in alt.cdrom-groups. that is what exellent customer-support is all about!

12/19/95 – I picked up your email address from a posting in the comp.publish.cdrom.hardware newsgroup. I will probably buy a HP 4020 soon and will need some software for it. Incat seem to be the best supported product through your own efforts.

1/11/96 – I am going to buy an HP CD Recorder, solely because of your presence and support on usenet. You take time to explain and help, and you know customer bitching is constructive feedback.

8/3/96 – the work that you do as a representative of Adaptec and your postings to the news groups are invaluable and more companies would be wise offer the quality support and time that you do.

5/14/96 – .Every once in a while, I log on to Compuserve and pore over the CDROM and CDVENB forums. I continue to be amazed at the thoughtful responses you give to the hundreds of messages that go by. You are doing a great job.

06-Nov-96 – I’d just like to congratulate you and your company on providing such detailed and helpful support online. Although I haven’t yet got a CD-R , I read these groups in preparation, and I’m always impressed at your helpful replies. This is the sort of service that other hardware/software suppliers would do well to emulate.

2/18/96 – I respect the effort you’re putting in to supporting Incat and Easy CD software. I see you all over CIS and the Internet and you’re always giving tips and help. I hope Incat knows all of this!!!

3/1/96 – …Its support like this that makes people choose your product over a competitor’s who dont use the net.

2/1/96 – BTW, I have been following this newsgroup for a few months now, and it’s nice to see a company rep getting involved on-line. Keep up the good work.

2/3/96 – I work in Pinnacle Micro Tech Support. I am glad you are up here fielding the flames tossed out.

1/24/96 – Thanks for the helpful response. I just started to monitor the comp.publish.cdrom.hardware and software news groups. I have seen several of your messages and look forward to seeing more as they seem to contain very useful information

Jul 25, 1997 – Newsgroups: comp.publish.cdrom.hardware

>That’s a good thing? A marketing person to advertise products instead

>of a technical person to help user. Hm.., which one do I like more?

Be fair. Deidre does help people here and at adptec mailing list I don’t know his technical background but he surely isn’t a marketing guy. Adaptec having a person looking at newsgroups and helping people using adaptec’s products is a good(and smart) movement. I wish other companies did the same (for ours and their own good).

15 Aug 1998 – Thank you for being on this USENET group… I appreciate the fact that Adaptec is a company that cares enough about its products and customer service to have a representative here. You have shown great patience and great restraint – there are several people on this NG whom I would have throttled by now if they were giving me the flak they are giving you.

You should be commended. It’s a thankless job, but I want to thank you. As a result of this, I will put Adaptec products at the top of my shopping list from now on.

6 May 1998

Dave Ulmer wrote: I realize that I’ll probably attract a lot of flamers with such statements and candor, but so be it. For those of you out there who know Deirdre, myself, and the ever-lurking development crew, I think you understand the efforts we undertake to be responsive and proactive, and that we’re not big, bad, bureaucrats, but a collection of individuals who stand by our customers and really do strive to make CD-Recording easier, more reliable, and what YOU want.

Yes, Deirdre is really a masthead for you company! I had serious trouble trying to upgrade my by HP request crippled Easy CD Pro to the NT4 friendly version during the special rebate offer. I sent repeated emails to your sales dept that went unanswered (due to understaffing at the time…), but my plea to her magically produced the chance to get the upgrade before the curtain was lowered. As a subscriber to the “A_CDR” mailing list, I am even more impressed by her efforts (have you reappraised her salary recently? There exist other companies that would need such a resource…)

24 Nov 1999 – How many other newsgroups have representatives from companies tapping in and helping / defending products? Adrian’s coming in here amongst a crowd of folks demanding answers and he’s handling it all quite well.

Subject: Re: De-Commercialization of News Groups

30 Nov 1999 – Newsgroups: comp.publish.cdrom.software, comp.publish.cdrom.hardware, alt.comp.periphs.cdr, alt.cd-rom

I welcome the presence of Adrian, for the most part. D’ is okay too, but she really never posts anything of End User Value. It is more of a facade or show than anything helpful. She does keep us up to date via e-mail, but that signature tag is almost as big as her e-mail. =)

If Adaptec wants to help out people in this news group, then I say they are warmly welcomed, if they do not attempt to mislead. Give support where needed, like Adrian has done.

I would ask that Adaptec’s Representative, Adrian, to stay in the news group. There are no other company’s reps out here trying to help end users. I think highly of Adaptec attempting to do the same.

So. If Adaptec is straight with the posters from the get-go, and keeps their positive role about them, I see no commercialization.

Subject: Thank you. – Date: Tue, 10 Jul 2001

I just wanted to express my thanks to both you and Adrian Miller. Adrian had helped me quite some time ago with a problem I was having, by responding to the article I posted in the alt.comp.periphs.cdr newsgroup.

I’m just felt like writing this now, as I have become appalled by the large onslaught of personal attacks the two of you have had to graciously endure in the said group. Why these people have nothing better to do than constantly berate you, and Roxio for no substantial reason is far beyond me. I just wanted to say there are in fact many of us who appreciate the work you do. Thank you.

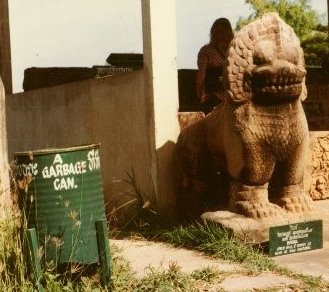

Funny Sign: A Garbage Can

Every item in this outdoor museum in Thailand is clearly and carefully labelled, in two languages.

Reflections on Machismo: “Fierce Invalids Home from Hot Climates”

Tom Robbins has long been one of my favorite authors; every one of his seven novels is a gem, infused with his uniquely loopy sensibility and style. This novel (Amazon UK | US), published in May, 2000, was eerily timely in its discussion of West vs. East and Muslim vs. Christian, in the context of a story about a renegade CIA agent, an Amazonian curse, the third prophecy of Fatima, and a band of excommunicated nuns in the Syrian desert. Among many other things, Robbins glances at a topic which has long puzzled me:

“…the sexual insecurities that among men of the Middle East achieved titanic, even earth-changing proportions; insecurities that had spawned veils, shaven heads, clitoridectomies, house arrest, segregation, macho posturing, and three major religions.”

Many of the world’s cultures and religions focus to an amazing degree on controlling women, and especially women’s sexuality. (As Robbins points out, it’s a global phenomenon: “The Levant had no monopoly on penile insecurity.”) It is true that much of this nastiness is enforced by women themselves upon their daughters unto the nth generation, but it’s all intended to “benefit” the men.

For example, the “logic” behind clitoridectomy is that, if a woman can’t enjoy sex, she won’t go looking for it outside of marriage. Less brutal methods for ensuring fidelity include covering her up so no one sees her, and and locking her up so she never gets the chance. In many cultures, the punishments for a woman’s infidelity (or even imagined infidelity) are far more severe than for men: death by stoning, murder by the husband and his family, or societally-condoned mutilation.

I guess these men are all afraid that they just aren’t man enough to keep their women satisfied.

Italy has a reputation (in America, at least) as having a “macho” culture, but this doesn’t work the way macho does in other places. Most Italian men would rather prove their virility by seduction than by force. Every now and then some silly pollster does a Europe-wide or worldwide survey on “who’s the best at…” Italians are generally rated the best lovers, a result widely reported in the Italian press. ; )

I’ve met a young Irish woman working in Milan as an au pair. Recently she and three friends were out drinking at a bar. One was mildly propositioned by a man, whom she turned down. Later, apparently, something was slipped into their drinks. The woman who had been propositioned has confused memories of winding up somewhere with the guy, with her pants off, but when she said “No,” he desisted. She and another of the women then slept all weekend, leading them to believe they had been drugged. When they confronted the man a few days later, he looked guilty, but pointed out that they couldn’t prove anything.

I’d never heard of this “date rape drug,” though it’s apparently well known elsewhere, and a fairly common danger in some parts of the world. The Irish woman told me that, home in Ireland, she would never touch a drink in a pub or disco unless she’s seen it poured and picked it up from the bar herself.

I told the story to some Italian women, and they agreed that this is a highly unusual event in Italy. The reason they gave was an insight into the culture: “No Italian man would want to go to bed with a woman unless he’d earned her.”

Pope-O-Vision

As popes go, John Paul II is certainly one of the best there’s ever been: he is truly upright and deeply religious, and he has tried to use his position to be a force for good in the world. I respect that, even though I’m not Catholic and don’t agree with everything he says.

But in Italy (as I often joke) we don’t have television, we have Pope-o-vision. Every day the news wires and TV report what the Pope is doing, or what he has to say about the global crisis or disaster of the day. But what he says is usually so predictable! Of course he’s going to pray for peace between the warring factions, for international understanding, for aid to the afflicted, etc. While kind and worthy, this is hardly news: he’s the Pope – what else would we expect him to say?

Occasionally he does come out with something surprising. For example: In Italy, many couples split up without officially filing for divorce (because it’s a huge, expensive hassle), and often the ex-partners end up living and even having children with someone new. The Pope declared that it was all right for these de facto new couples to take communion – as long as they weren’t actually having sex.

The Italian media’s obsession with the Pope is baffling, because so few Italians today are devoutly practicing Catholics. Evidence: The vast majority of Italians are nominally Catholic, and the Church does not believe in “unnatural” forms of birth control, yet Italy has one of the world’s lowest birthrates. (Followed closely by that other very Catholic country, Spain.)

Italy’s shift to secularity is recent. Divorce became legal only in 1970, in a parliamentary decision which the Vatican attempted to overturn by a national referendum in 1974. To the shock of the Church, 60% of the Italian people voted in favor of keeping divorce legal. Similarly, and even more strikingly, a 1978 law making abortion legal was brought to referendum in 1981, and again the Church and its political friends failed: the right to abortion was sustained by 68% of Italians. Since then, abortion has never been a serious political issue in Italy.

Returning to my original topic: My irreverence towards the Church (and indeed all religious institutions) is partly my own, but I’ve also absorbed it from the Italians, many of whom, in spite of their media’s obsessions, don’t take Catholicism as an institution very seriously. They’ve had a ringside seat on the Vatican’s activities for most of 2000 years, and they know how little the Church-with-a-capital-C has had to do with religion for much of that time.