Childhood

As a child, I was accustomed to drawing attention because I looked different from most of the people around me: I lived in Bangkok, where Thai women were constantly pinching my cheeks and exclaiming over my fair skin and blonde hair. I assumed they were merely intrigued because I looked strange to them. I didn’t think much about my looks one way or the other; I’m not sure whether that was unusual for a girl of my generation.

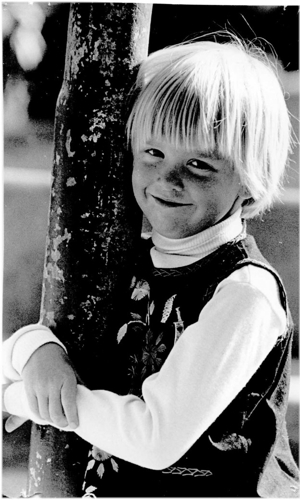

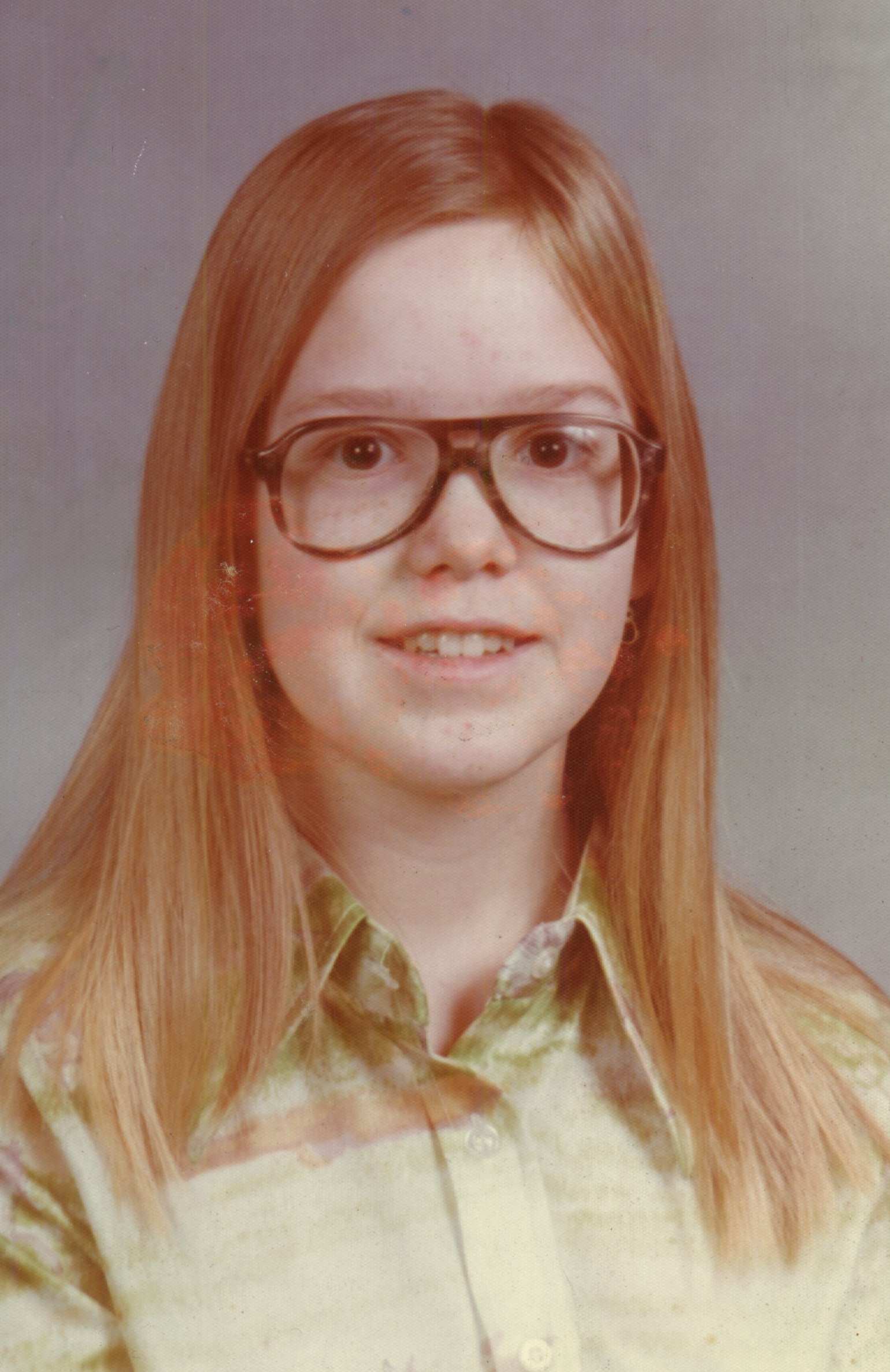

Then, around age eight, I started wearing glasses. Glasses weren’t cool in those days, and there weren’t many style choices, especially in kids’ sizes:

^ these were called granny glasses – just what a 9 year old wants!

Through the 70s and 80s, glasses styles just got worse.Then there was my hair…

Fine, blonde, and uncompromisingly straight, it would have been “the look” in hippie days. But in the big hair era, it refused to respond to curling irons, and was badly damaged when I tried having it permed.

All this is by way of saying that, during those crucial teenage and young adult years, I rarely had any sense of myself as attractive. Shy and geeky, I also didn’t have the outgoing personality that gains a not-conventionally-attractive girl attention. Nevertheless, I briefly had a sweetheart in 7th grade, until our classmates teased us so much that being together was not worth the bullying.

I was 13 and somewhat behind the development curve of my American peers when my family moved to Bangladesh. During my year there and subsequent four years at boarding school in India, I grew accustomed to either too much male attention, of the wrong sort, or none at all. At school, it seemed as if every boy I got a crush on immediately became interested in some other girl, without ever noticing me.

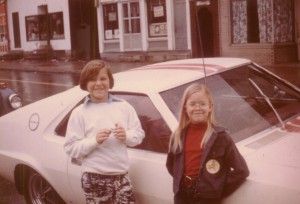

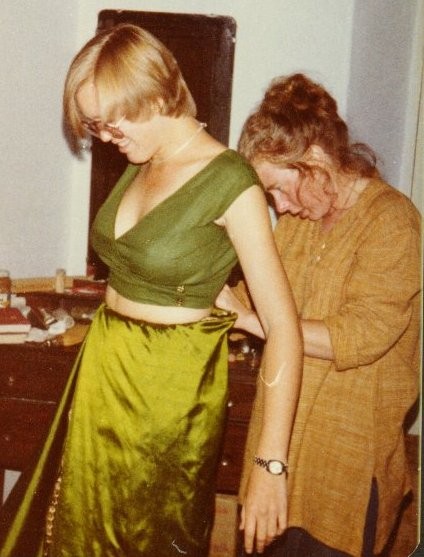

Okay, yes, I eventually grew into this body:

…but I was growing up in India, where local standards of modesty required women’s bodies to be covered by loose clothing.

Woman and Wife

We judge our own looks by the looks of the people we are able to attract. “S/he’s out of your league,” we tell ourselves. Or we feel smug when someone whom the world acknowledges to be hot thinks we’re hot, too. I had a cute boyfriend my first year in college, but my fundamental geekiness kept me out of further relationships until Enrico. Who was (and is) very handsome. Was I in his league? Well, he liked my body, but wanted everything else to change: I should wear contacts instead of glasses, and grow my hair long. This is why, in my wedding pictures, I didn’t look much like the me of before.

Or after. The contacts were a failed experiment: my eyes are too dry and allergic. My fine hair, when long, simply becomes limp. Though I lost my pregnancy weight within a year or two, I ended up heavier than when I got married – and so did Enrico. This seems to happen to a lot of married people. Age? Laziness? Complacency? Or maybe just feeling that no one actually cared what I looked like. I put on a lot more weight when I started traveling for Sun and spending more time in the US: by mid-2008 I weighed around 170 lbs.

Weight aside, I was learning how to look better.

Weight loss is a well-known consequence of divorce. In my case, it could have been taken as an early warning sign. I left Italy in March, 2008, but at the time was not ready to acknowledge that my marriage was effectively over. By January, 2009, I had begun to lose weight, without even trying very hard.

In August, 2009, Enrico and I went on a road trip together to some of the great national parks of the US southwest. I think we both knew this would be the end. We had largely failed to celebrate our 20th anniversary on May 28th of that year, even though we had been geographically together that day: we went out to dinner and he bought me some beautful jewelry – my friend Sue forced him to.

Though I still weighed close to 160 lbs, I was, I thought, looking pretty good. Others had been letting me know that they thought so, too – a novel experience for me. At a Gap store in Aspen, I tried on a miniskirt and low-cut shirt. I twirled in front of Enrico, looking for a compliment – something he had not given easily for years.

“How do I look?” I demanded.

“You’re holding up better than any other 46-year-old I know,” he grudgingly admitted.

Twitter forces me to realize that this incident was confused in my memory with a later one, when I actually put on that outfit to go out to dinner. After days of hot, dusty driving and hiking, staying in cheap motels, we spent two nights at Bally’s hotel in Las Vegas, and I wanted to celebrate the relative luxury. Cleaned up, made up, dressed up in my new clothes, I once again tried for a compliment, some acknowledgement that my husband of 20 years still felt any spark of attraction to me.

The silence stretched. He seemed to be going through an immense inner struggle, as if to say anything nice to me would somehow cede power in the relationship. I don’t remember what he finally said, but, in that long pause, I knew that my marriage was over. I went to bed angry that night, and woke up thinking: “I can’t care anymore what he thinks, it hurts too much.” By the end of the month we had had “the conversation.” Of course this was far from the only factor in our breakup, but it’s important to feel that your partner finds you attractive – and I hadn’t felt that for a long, long time.

Here and Now

I’ll be 50 in November, and I’ve never looked better (for one thing, I dropped another 20 pounds). I’m still not used to the idea but, actually, I look pretty damned good. Which is an unexpected gift at this stage in my life. Will it last? Of course not, at least not in its present form. I may always look “better” than some average of women my age or women in general, but I will certainly age. The alternative is to die young (which I’m currently trying to avoid).

The Future

What about what Belle de Jour once called “the cycle of self-hatred and frantic desperation that plagues many women as they age”?

To me, having beauty feels a bit like having money once did. Twelve years ago, at the crest of the dot com boom, I was making (for me) awfully good money. I flew business class from Milan to California four times a year. I took my family on vacations to the Caribbean and out to eat in expensive restaurants. And I wondered: would I feel bad about myself when the good times stopped rolling?

Which they did. From 2001 to 2007 I spent down my savings as I was less and less able to find meaningful and gainful employment in Italy. I was frustrated and didn’t like going broke, but I didn’t feel any worse about myself. I prefer the security and ease of mind of having money, but it doesn’t define who I am; lacking money doesn’t affect my sense of self-worth (though it causes other stresses).

I hope and expect that I’ll feel the same way about my looks. I’m enjoying what I have now, but it doesn’t affect who I am. Indeed, feeling confident that I am a worthy and interesting person independent of my looks probably contributes to my attractiveness, and that kind of confidence tends to come to women only with age, regardless of whether they grew up beautiful.

Update

Headshots from a portrait session with Shawn Northcutt, April 2013: