Last September I joined the Slow Foodassociation, dedicated to the appreciation and conservation of good food worldwide. We’ve been to three dinners so far, two of which emphasized wine, and one in which every dish somehow involved chocolate. The wine dinners also featured excellent food, and vice-versa. The international Slow Food association is divided into local groups, in Italy called condotte. Outside of Italy they’re called convivia, which fits: after you’ve been drinking good wine together for an hour or so, everyone does get very convivial!

The most recent dinner we attended began with a tasting of Sfursat, a wine from Valtellina, an Alpine valley northeast of Lake Como. Sfursat (dialect for sforzato – “forced”) is made by drying the harvested grapes for three months before pressing, so that their sugar content – and therefore the percentage of alcohol in the wine – is high, at least 14.5%.

The best of the four Sfursat we tasted that night was Sfursat 5 Stelle from the Nino Negri vineyard, and we had the privilege of sharing a dinner table with Casimiro Maule’, the vintner who created it. He told us a great deal about winemaking in Valtellina, most of which I can’t remember (too many glasses of Sfursat and other grand Valtellina wines!). I do remember that it’s difficult to grow wine there; the terrain is steeply mountainous and the soil not extremely fertile. But Sig. Maule’s Sfursat, and other excellent wines from the region, prove that it can be done, and done very well indeed.

I’m not sure how easy it is to obtain Valtellina wines outside of Italy, but if you love good wine, it would be worth the effort to track them down or demand them from your local supplier. A more common type is called Inferno – yes, it’s a hell of a wine. A good example of this is Giuseppe Rainoldi’s Inferno Barrique, which has a wonderful complex flavor because it’s aged in small wooden casks.

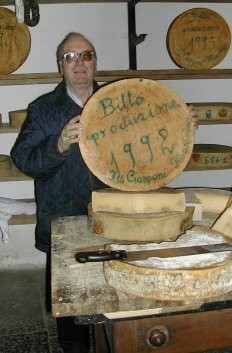

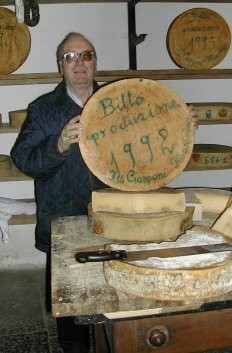

In the spirit of Slow Food, last week Enrico and I explored Valtellina, making our first stop in Morbegno at the renowned shop of Fratelli Ciapponi. We spent two hours there with one of the senior brothers Ciapponi, taking a tour of the shop and its underground wine and cheese rooms, and got a complete explanation of how the local bitto cheese is made and successfully matured. (“I caress these cheeses more than I do my wife,” said Sig. Ciapponi, probably not for the first time.) We tastedbitto of various ages. There were noticeable differences at one, two, and six years, partly due to ageing, but also because this is a handcrafted cheese that depends heavily on environmental conditions: more rainfall means better grass in the high Alpine pastures, and tastier milk from the cows and goats who produce the raw materials.

Sated with cheese, we continued on our way to Bormio, a ski resort town. I don’t ski, and it’s been a bad season for skiing anyway, so why did we go there? For the natural hot spring spas. These date back at least to the Romans; Pliny the Elder described the baths in the first century AD. The Bagni Vecchi (“Old Baths”) have been expanded and refurbished over 2000 years to their present glorious state, which includes:

- a 30-meter y-shaped tunnel dug into the mountain, debouching into a natural steam room on one side and a channel full of very hot (46 Celsius) water on the other

- pools with hot waterfalls – natural massage!

- mud baths

- steam rooms and saunas

- an outdoor hot water pool with a view of the mountains all around

It was heaven. We spent all afternoon there, and I went back the next day while Enrico went skiing. If you love to get into hot water, this is the place to do it.

Caveat: The Bagni Vecchi are closed in May, and in the summer the water is not nearly so warm – for some odd geothermal reason, when the ground freezes, the water gets hotter. Best and least crowded times to go are probably November before the ski season really gets underway, and March/April when the season is ending.