Lately I’ve been doing a lot of research about love, relationships, marriage, and divorce. I’m still mystified – and so are the experts. But new technology (fMRI) allows us to look inside the brain in new ways, so perhaps we are finally on the road to explaining the great “mystery of love” which has puzzled philosophers, psychologists, and lovers, probably since the dawn of human consciousness.

Here’s what I’ve learned so far:

Dr. Helen Fisher postulates (and researches) the theory that humans have evolved three kinds of mating-related love, each driven by separate (but connected) hormonal circuits in the brain:

- Lust (associated with testosterone) drives us to mate (well, duh, otherwise the species wouldn’t be here).

- Romantic love (dopamine) is a drive – rather than an emotion – which focuses our attention on one person who could potentially be a long-term mate. Focus is the key word here: many of the symptoms of intense romantic love are manifestations of obsessive focus on the object of that love.

- Attachment (vasopressin, oxytocin) is a feeling of calm and security, which encourages us to stay with a mate long enough to raise a child.*

Fisher says it is possible to feel any of these three types of love in any combination or order, and to feel each for different people at the same time, though she also states that it is not possible to feel romantic love for more than one person at a time (presumably because of the intense focus involved).

Each type of love can (though it doesn’t necessarily) lead to another: lustful stimulation of the genitals causes dopamine to be produced, triggering romantic love. Orgasm causes a flood of oxytocin and vasopressin, which can lead to attachment, especially when repeated. Conversely, feelings of attachment can morph into romantic love: the “falling in love with your best friend” phenomenon.

Note that, in Fisher’s scenario, the term “real love” is meaningless. If you’re feeling it – and not just pretending to yourself or someone else that you are – it’s real. The important question is: which kind of love are you feeling?

The Evolution of Love

In Anatomy of Love: A Natural History of Mating, Marriage, and Why We Stray (1994, updated 2016), Fisher postulates that walking on two legs forced humans to evolve pair bonding. Unlike an ape, whose baby rides on its mother’s back, an upright, bipedal human must carry her (far more helpless) baby in her arms or on her hip. This means that she cannot easily run from predators, take refuge in a tree, or forage for her food. She needs a mate for protection, to help ensure the survival of herself and her child. A male who bonds with a female and helps care for their child ensures that his genes survive and are carried on. So we are selected for pairing up (temporarily) to bear and raise children.

BUT – Fisher believes that: “Humans have evolved a dual reproductive strategy: a drive to pair up to raise children, but also a restlessness and tendency to adultery, divorce, and remarriage.” (quoted from her talk at LeWeb ’08, though the point is also made in her books).

Many species besides humans are monogamous, and for similar reasons: it takes two to successfully raise young. But genetic studies have shown that most “monogamous” species – even those that bond only for a single mating season – are also adulterous.

This behavior has evolved because both sexes are trying to get the best of both genetic worlds. It’s to the female’s advantage to have a steady mate to help raise the young, but she also benefits from having offspring with a genetic variety of males, which gives her own genes a better chance of surviving and being carried on. It’s to the male’s genetic advantage to impregnate as many females as possible, while investing the minimum resources in actually raising the resulting offspring.

Conversely, each has a strong interest in ensuring that their partner does not stray: the male does not want to be tricked into raising some other male’s children, while the female does not want her mate spending resources on some other female, or possibly being lured away for good, leaving her to raise their offspring alone. Hence the irrational, sometimes overwhelming, power of jealousy.

Fisher reports on studies showing that, in pre-agricultural hunter-gatherer societies, where the sexes have similar “economic” (food gathering) power, pair bonds were/are not expected to last for life. Divorce, though painful, is not difficult: either partner can easily walk away with all of his/her possessions, to start a new life with a new partner.

Fisher believes that humankind’s invention of agriculture made women dependent on men, because plowing required a man’s strength. But a man could not manage a farm alone, nor could land be parceled out and carried away if a relationship ended. “Til death do us part” became the norm for good reason: losing a mate could be fatal.

This ancient “ideal” still carries enormous cultural weight, even though most of us today are not farmers and may not even need a partner for economic support.

Love Today

I distill from all this that modern humans are subject to several warring impulses:

- We are evolved to mate (just) long enough to produce and raise offspring.

- Both sexes are also evolved to cheat, but we mostly do it on the sly because it is enormously threatening to our mates.

- Much more recently in human evolutionary history, but long ago in cultural memory, we developed a societal expectation that we will mate with absolute fidelity and forever. It’s important to realize that this expectation is cultural, not evolved.

The prevailing attitude towards love and marriage in American culture is particularly and dangerously idealized. We define “real” love as romance that grows into a lifelong, sexually-faithful attachment. Marriage is further burdened with expectations that our partner will meet our every emotional and physical need, and that, if the love is “real”, we will live together harmoniously forever and ever, amen.

The expected pattern is that you meet “the one,” fall in love, marry, have children, and live happily ever after. Popular culture (from romance novels to chick flicks to self-help books to greeting cards) constantly reinforces this, so we feel cheated or that we have failed if we do not experience this kind of idealized, all-encompassing love – or if it doesn’t last forever.

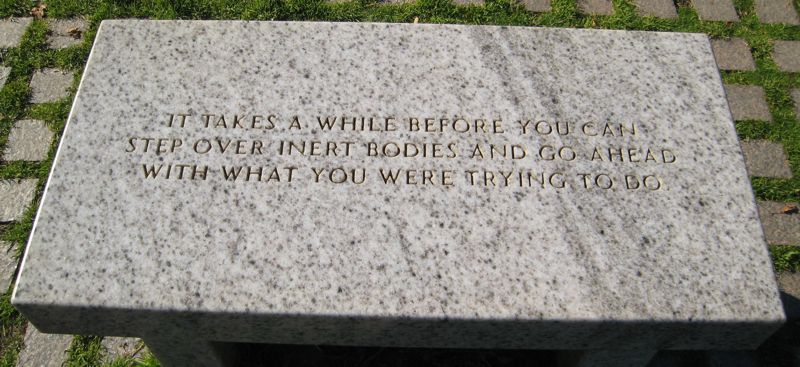

It seems to me that this American myth of love does more harm than good. We go into marriage expecting far too much of the relationship and of our spouse, and blame them or ourselves when the reality falls short of our expectations. We feel pressured to “make it work” even when one or both partners is irremediably unhappy in a relationship. We feel crushing guilt when a relationship fails. Then we go out searching all over again for “that special someone” to fulfill an impossible ideal, kicking off another cycle of inevitable disappointment.

…and that’s what I’ve figured out so far. Your thoughts?

Related reading:

- Why Him? Why Her?: Finding Real Love By Understanding Your Personality Type

- Why We Love: The Nature and Chemistry of Romantic Love

- The Female Brain

- Crazy Time: Surviving Divorce and Building a New Life

- Coming Apart: Why Relationships End and How to Live Through the Ending of Yours

- The Myth of Monogamy: Fidelity and Infidelity in Animals and People

* According to Fisher, in pre-agricultural societies “long enough to raise a child” is/was probably about four years. More on that another time.