As sponsors of the SC09 Broader Engagement initiative, and because we gave such a great party last year, we were asked to sponsor a party again this year for students attending SC09. For a number of reasons we weren’t able to commit to this until the last minute, so thanks to Tiki Suarez-Brown and Tony Baylis of the Broader Engagement program for their patience and considerable effort in making sure this took place.

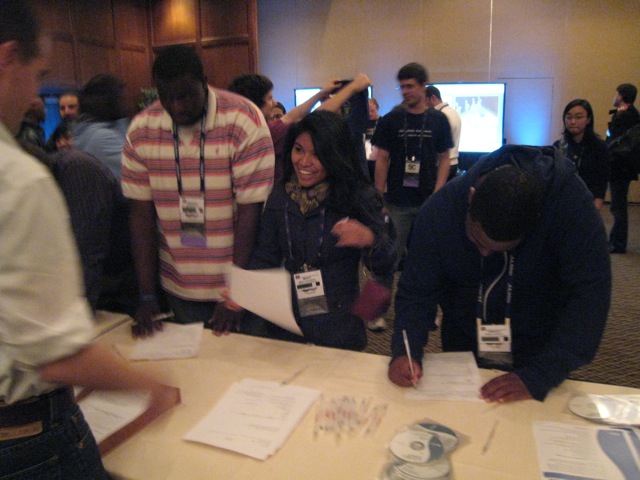

Because it was so last-minute, this year’s party was much more low-key than last year’s, but seems to have been appreciated by the ~250 students and educators who attended. They arrived around 7 pm after a full day of other activities, and were mostly glad to relax, eat a good dinner, and chat.

Everyone who attended had the option to fill in a brief survey in return for an OpenSolaris t-shirt and the chance to win an iPod in a drawing later in the evening. No one minded doing the “work” – we used up almost all of the 250 surveys we had printed.

For entertainment, we had two rented Nintendo Wii systems, which many enjoyed.

The event was also an opportunity for Sun folks to meet and talk with students and educators (potential future collaborators and colleagues!). The Sun folks introduced themselves from a small stage at the end of the room, and, as last year, stayed busy all evening conversing with our guests.

Above, Sun’s Josh Simon’s plays Wii archery with students. As you can see, some people put on their OpenSolaris t-shirts immediately.