Old Days, Old Ways: Adaptec

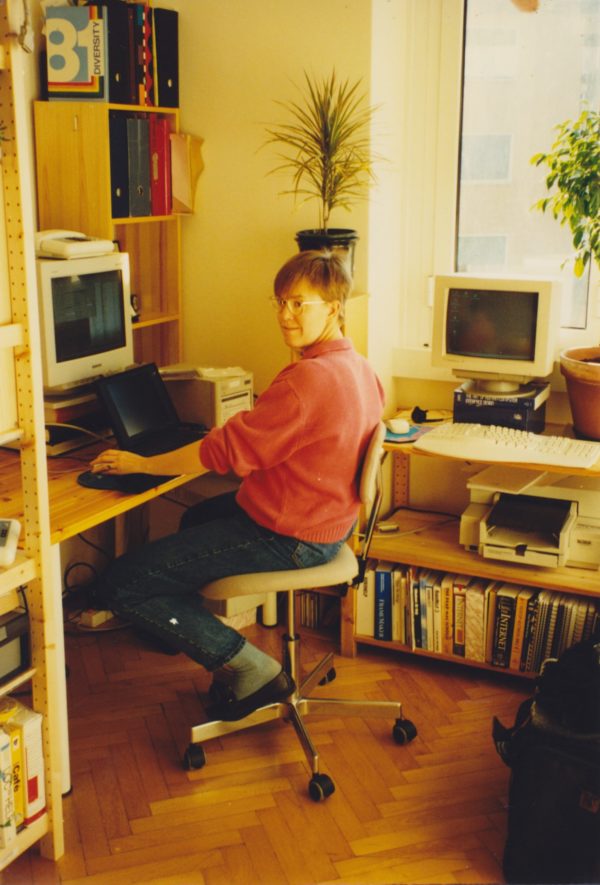

When I began working for Adaptec in 1995 (as a result of their acquisition of Incat Systems, the company which created Easy CD), I was already a remote worker. Fabrizio Caffarelli, who had founded Incat in Milan, had moved himself and the engineering staff to California in late 1993 with the goal of selling the company. In the meantime, though still living in Milan, I needed to work closely with engineering staff to document, test, and help to improve our software products. I began traveling to California regularly, but most of the time I worked from home, keeping in touch by phone and email.

Nobody at Incat had a problem with this, but the concept was foreign to Adaptec back then. In 1995, they had not even had email for very long because (so I was told) the company’s executives had resisted, fearing it would be “a distraction” (they may have had a point).

Adaptec at the time did not have any employees working permanently offsite, and they were not about to make exceptions for an unknown quantity like me so, in spite of my clearly-stated preference to become a “regular” Adaptec employee, I was taken on only as a contractor.

Adaptec’s employee benefits would not actually have been all that interesting or useful to me (e.g., I didn’t need US health insurance). However, although even the regular employees had California-standard “at will” contracts, I suspected that, as a contractor, I was more vulnerable than they to cyclical layoffs.

Some people at Adaptec even treated me as an outsider – not realizing (or perhaps resenting) that, to the CD-recording world, I was the face of Adaptec online.

On one memorable occasion, a customer reported to me that he had phoned tech support, quoting me on some technical question.

“Oh, she doesn’t know what she’s talking about,” responded the tech. “She’s just a consultant.”

I also had the uneasy feeling that, even among some of the people I worked most closely with, I wasn’t perceived as being part of the team, nor as being serious about my career. Part of the reason I started an MBA (via distance learning, of course!) was to demonstrate my seriousness – had I had to apply for the job I was already doing, the job description would have included “MBA strongly preferred.”

While I was doing one of my first MBA courses, an engineering colleague from Adaptec’s Longmont, CO office, Dan Maslowski, came up against a personal situation: he was perfectly happy in his job, but his wife had been offered the opportunity to open the European offices of the (Web) company she was working for.

Dan’s boss didn’t want to lose him, but wasn’t sure how to deal with a remote employee. So they talked to me, as an example of how it could be done, and Dan eventually moved to the Hague while still working for Adaptec. We were a mutual support society of two, commiserating on how difficult it was (and still is) to schedule phone conferences when you’re eight or nine time zones away from everyone else. I even wrote him up as a case study for my MBA course.

My own situation with Adaptec endured, but several changes of manager back at headquarters increased my sense of vulnerability, frustration, and alienation. From some perspectives, I had an ideal job: I could set my own hours (as long as those included lots of late-night phone conferences), and was largely managing my own work and that of two other contractors, all of us working from our respective homes.

But I was at a career dead-end. It was clear that, with Adaptec, I could never become a regular employee, let alone have a career path, as long as I was off-site. I was good at what I was doing, but had been doing it long enough to be getting bored. I could see things that (desperately) needed changing to make life better for Adaptec’s customers, but I would never be in a position to make those changes happen.

Hence my attempted move to California in 2000-2001, to participate in the Roxio spin-off. I wanted to help define, from the ground up, how a new company would deal with its customers, using the Internet as a tool for support, marketing, and relationship-building via customer communities.

I planned to move my family to the US for a year or two – long enough, I hoped, for me to launch a career and then find a way to move back to Italy, where my husband had his own career that he was not willing to give up.

That didn’t quite work out. The whole Roxio situation went sour for me, and I returned to Milan in March, 2001 – back to the same situation in which I had previously felt so vulnerable, alienated, and frustrated.

All those same adjectives still obtained, redoubled. The (ridiculously good) money was not enough to overcome my misery, especially when my mother-in-law was diagnosed with breast cancer. I didn’t think I could handle a major family crisis while hating my job every day. I quit in July, 2001. (My mother-in-law was successfully treated for the cancer and is still living; Roxio is no longer with us).

A New Dawn: Sun Microsystems

Corporate practice and technology have naturally moved on, and working remotely no longer seems as strange or difficult as it did ten years ago (although in Italy it’s still highly unusual). Having suffered through the early days with a resistant employer, I am now delighted to find myself working with a company that gets it.

Remember Dan? He ended up working for Sun Microsystems, where he’s currently a Senior Engineering Manager. When he realized in February that the new position he had just taken on entailed responsibilities for part of a website, he thought of me.

I knew nothing about Sun, except that Dan worked there and I liked what I could see of his management style. He had even left Sun for AMD, then gone back to Sun, and they’d kept his company blog waiting for him. This is standard practice at Sun (10% of whose ~33,000 employees have blogs open to the public), and is a subtle indicator of the company’s relationship with its people.

Obviously, Dan was asking me to join him knowing that I live in Italy and, though very willing to travel, this is where I’ll be staying. It didn’t occur to me to ask whether this would be a problem; his answer would have been: Of course not.

His team was already spread across time zones from Silicon Valley to Beijing, so managing one more person in one more location wasn’t going to make much difference to him.

Arriving at Sun’s offices in Broomfield, CO for a first meet-and-greet visit in March, I astonished to learn that practically all of Sun is like this: teams seem to be formed on no geographical basis whatsoever, and many Sun employees work from home, wherever home may be. According to an official company statement I heard in an online presentation for newbies, at least 50% of Sun employees work from home at least one or two days a week.

This point was made most forcefully for me when I read the first blog post from Deb Smith, a Director in the software group I’m working for. Go read that now and you’ll see what I mean. As soon as I read it, I thought: I’m in the right place.

The whole company is built for what they call OpenWork, with all the right systems – and, more importantly, attitudes – in place to make it work well both for the company and its employees.

This is probably a factor in the large proportion of women who stay with Sun – I’ve never seen so many women in an engineering organization!

And it’s not just the women: practically everyone at Sun seems to have been there for at least ten years (the company celebrates its 25th anniversary this year), with no intention of leaving. Upon getting to know Sun a little better, this does not surprise me at all. Sun demonstrates that it values its people, and understands the importance to those people of all aspects of their lives, not just their careers. That sounds like an organization I’d like to stick with.

what qualities do you look for in an employer?